East Asian Yogācāra

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese Buddhism |

|---|

|

East Asian Yogācāra refers to the Mahayana Buddhist traditions in East Asia which developed out of the Indian Buddhist Yogācāra (lit. "yogic practice") systems (also known as Vijñānavāda, "the doctrine of consciousness" or Cittamātra, "mind-only"). In East Asian Buddhism, this school of Buddhist idealism was known as the "Consciousness-Only school" (traditional Chinese: 唯識宗; ; pinyin: Wéishí-zōng; Japanese pronunciation: Yuishiki-shū; Korean: 유식종).

The 4th-century Gandharan brothers, Asaṅga and Vasubandhu, are considered the classic founders of Indian Yogacara school.[1] The East Asian tradition developed through the work of numerous Buddhist thinkers working in Chinese. They include Bodhiruci, Ratnamati, Huiguang, Paramārtha, Jingying Huiyuan, Zhiyan, Xuanzang and his students Kuiji, Woncheuk and Dōshō.

The East Asian consciousness only school is traditionally seen as being divided into two main branches. There is the Dharma nature schools (Fǎxìng zōng, 法性), which refers to the earliest traditions to develop in China, like Dilun and Shelun, as well as to their specific doctrinal position which often blends buddha-nature thought with Yogācāra. The other branch is the "Dharma Characteristics school" (Fǎxiàng-zōng), which is mostly used to refer specifically to the tradition of Xuanzang and tends to focus much more strictly on mainstream Yogācāra philosophy.[2]

Names

[edit]In Chinese Buddhism, the overall Yogācāra tradition is mostly called Wéishí-zōng (traditional Chinese: 唯識宗; ; Japanese pronunciation: Yuishiki-shū; Korean: 유식종, yusik) which is a translation of the Sanskrit Vijñānavādin ("cognition only", "mere consciousness"). The consciousness-only view is the central philosophical tenet of the school which states that ontologically there are only vijñāna (consciousness, mental events).

Yogācāra may also be referred to as Yújiāxíng Pài (瑜伽行派), a direct translation of the Sanskrit term Yogācāra ("Yogic praxis").

The term Fǎxiàng-zōng ("dharma characteristics", traditional Chinese: 法相宗; ; Japanese pronunciation: Hossō-shū; Korean: 법상종) was first applied to a branch of Yogacara by the Huayan scholar Chengguan, who used it to characterize the teachings of the school of Xuanzang and the Cheng Wei Shi Lun as provisional, dealing with the characteristics of phenomena or dharmas. As such, this name was an outside term used by critics of the school, which eventually was adopted by Weishi nevertheless. Another lesser known name for the school is Yǒu Zōng (有宗 "School of Existence"). Yin Shun also introduced a threefold classification for Buddhist teachings which designates this school as Xūwàng Wéishí Xì (虛妄唯識系 "False Imagination Mere Consciousness System").[3]

In opposition to the "Dharma characteristics" view, the term Dharma nature school (Fǎxìng zōng, 法性) is used to refer to a form of Yogācāra which blends Yogācāra with buddha-nature (tathagatagarbha) thought, especially with the doctrines of texts like the Awakening of Faith. This term would include schools like Dilun, Shelun, Chan, and Huayan, who affirm basic Yogācāra principles like mind-only, while also promoting metaphysical views which are not strictly compatible with orthodox Yogācāra.[2]

Characteristics

[edit]Like the Indian parent Yogācāra school, the East Asian Weishi tradition teaches that reality is only consciousness, and rejects the existence of mind-independent objects or matter. Instead, Weishi holds that all phenomena (dharmas) arise from the mind. In this tradition, deluded minds distort the ultimate truth, and project false appearances of independent subjects and objects (which is termed the imagined nature).[4]

In keeping with Indian Yogācāra tradition, Weishi divides the mind into Eight Consciousnesses and the Four Aspects of Cognition, which produce what we view as reality. The analysis of the eighth, the ālayavijñana, or store-consciousness (阿賴耶識) which is at the root of all experience, is a key feature of all forms of Weishi Buddhism. This root consciousness is also held to be the carrier of all karmic seeds (種子). Another central doctrinal schema for the Weishi traditions is the schema of the three natures (三性).

The central canonical texts of Weishi Buddhism are the classic Indian sutras associated with Yogācāra, such as the Saṃdhinirmocana-sūtra and the Daśabhūmikasūtra, as well as the works associated with Maitreya, Asanga and Vasubandhu, including the Yogācārabhūmi-śāstra, Mahāyānasaṃgraha, Viṃśatikā, Triṃśikā, and the Xianyang shengjiao lun (顯揚聖教論, T 1602.31.480b-583b).[5] Besides these Indic works, the Chéng Wéishì Lùn (成唯識論, The Demonstration of Consciousness-only) compiled by Xuanzang is also a key work of the tradition.

There are different sub-sects of the East Asian Weishi, including the early "Dharma-nature" schools such as Dilun and Shelun, the school of Xuanzang, as well as Korean and Japanese branches of Weishi.

History in mainland Asia

[edit]Translations of Indian Yogācāra texts were first introduced to China in the early fifth century.[6] Among these was Guṇabhadra's translation of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra in four fascicles, which would also become important in the early history of Chan Buddhism. Another early set of translations where two texts by Dharmakṣema (Ch: Tan Wuchen 曇無讖; 385–433): the Bodhisattvabhūmi-sūtra (Pusa di chi jing 菩薩地持經; Stages of the Bodhisattva Path), and the Bodhisattva Prātimokṣa (which contains excerpts from the Yogācārabhūmi).[7]

The earliest Yogacara traditions were the Dilun (Daśabhūmika) and Shelun (Mahāyānasaṃgraha) schools, which were based on Chinese translations of Indian Yogacara treatises. The Dilun and Shelun schools followed traditional Indian Yogacara teachings along with tathāgatagarbha (i.e. buddha-nature) teachings, and as such were really hybrids of Yogācāra and tathāgatagarbha.[8] While these schools were eventually eclipsed by other Chinese Buddhist traditions, their ideas were preserved and developed by later thinkers, including the Korean monks Woncheuk (c. 613–696) and Wohnyo, and the patriarchs of the Huayan school like Zhiyan (602–668), who himself studied under Dilun and Shelun masters and Fazang (643–712).[9]

Dilun school

[edit]The Dilun or Daśabhūmikā school (Sanskrit. Chinese: 地論宗; pinyin di lun zong, "School of the Treatise on the Bhūmis") was a tradition that derived from the translators Bodhiruci (Putiliuzhi 菩提流支; d. 527) and Ratnamati (Lenamoti 勒那摩提; d.u.). Both translators worked on Vasubandhu's Shidijing lun (十地經論, Sanskrit: *Daśabhūmi-vyākhyāna or *Daśabhūmika-sūtra-śāstra, "Commentary on the Daśabhūmikasūtra"), producing a translation during the Northern Wei.[8][10]

Bodhiruci and Ratnamati ended up disagreeing on how to interpret Yogacara doctrine and thus, this tradition eventually split into northern and southern schools. During the Northern and Southern Dynasties era this was the most popular Yogacara school. The northern school followed the interpretations and teachings of Bodhiruci (6th century CE) while the southern school followed Ratnamati.[8][10] Modern scholars argue that the influential treatise called the Awakening of Faith was written by someone in the northern Dilun tradition of Bodhiruci.[11] Ratnamati also translated the Ratnagotravibhāga (究竟一乘寶性論 Taisho no. 1611), an influential buddha-nature treatise.[12]

According to Hans-Rudolf Kantor, one of the most important doctrinal differences and points of contention between the southern and northern Dilun schools was "the question of whether the ālaya-consciousness is constituted of both reality and purity, and is identical with the pure mind (Southern Way), or whether it comprises exclusively falsehood, and is a mind of defilements giving rise to the unreal world of sentient beings (Northern Way)."[13]

According to Daochong (道寵), a student of Bodhiruci and the main representative of the northern school, the storehouse consciousness is not ultimately real and buddha-nature is something that one acquires only after attaining Buddhahood (that is, the storehouse consciousness ceases and transforms into the buddha-nature). On the other hand, the southern school of Ratnamatiʼs student Huiguang (慧光) held that the storehouse consciousness was real and synonymous with buddha-nature, which is immanent in all sentient beings like a jewel in a trash heap. Other important figures of the southern school were Huiguangʼs disciple Fashang (法上, 495–580), and Fashangʼs disciple Jingying Huiyuan (淨影慧遠, 523–592). This school's doctrine was later passed on to the Huayan school via Zhiyan.[14]

An important founding figure of the southern Dilun, Huiguang (468–537) was the leading disciple of Ratnamati, who composed various commentaries, including: Commentary on the Ten Grounds Sutra (十地論疏 (Shidilun shu), Commentary on the Flower Garland Sutra (華嚴經疏 Huayanjing shu), Commentary on the Nirvana Sutra (涅槃經疏 Niepanjing shu) and Commentary on the Sutra of Queen Srimala (人王經疏 Renwangjing shu).

Shelun school

[edit]During the sixth century CE, the Indian monk and translator Paramārtha (Zhendi 真諦; 499–569) widely propagated Yogācāra teachings in China. His translations include the Saṃdhinirmocana Sūtra, the Madhyāntavibhāga-kārikā, the Triṃśikā-vijñaptimātratā, Dignāga’s Ālambana-parīkṣā (Wu xiang si chen lun 無相思塵論), the Mahāyānasaṃgraha and the Viniścayasaṃgrahaṇī (Juedingzang lun 決定藏論; a part of the a Yogācārabhūmi-śāstra).[10][15] Paramārtha also taught widely on the principles of Consciousness Only, and developed a large following in southern China. Many monks and laypeople traveled long distances to hear his teachings, especially those on the Mahāyānasaṃgraha.[15] This tradition was known as the Shelun school (摂論宗, Shelun zong).[16]

The most distinctive teaching of this school was the doctrine of the "pure consciousness" or "immaculate consciousness" (amalavijñāna, Ch: amoluoshi 阿摩羅識 or wugou shi 無垢識).[17][18][19] Paramārtha taught that there was a pure and permanent (nitya) consciousness that is unaffected by suffering or mental afflictions, is not a basis for the defilements (unlike the ālayavijñāna), but rather is a basis for the noble path (āryamārga).[17] Thus, the immaculate consciousness is the purifying counteragent to all the defilements.[17] According to Paramārtha, at the moment of enlightenment, one experiences a “transformation of the basis” (āśrayaparāvṛtti) which leads to the cessation of the storehouse consciousness, leaving only the immaculate consciousness.[17] Some texts attributed to Paramārtha also state that the perfected nature (pariniṣpannasvabhāva) is equivalent to the amalavijñāna.[17] Furthermore, some sources attributed to Paramārtha also identify the immaculate consciousness with the “innate purity of the mind” (prakṛtiprabhāsvaracitta), which links the idea with the doctrine of Buddha nature.[17]

Xuanzang's school

[edit]

By the time of Xuanzang (602 – 664), Yogācāra teachings had already been propagated widely in China, but there were many conflicting interpretations among the different schools. At the age of 33, Xuanzang made a dangerous journey to India in order to study Buddhism there and to procure Buddhist texts for translation into Chinese.[20] He sought to put an end to the various debates in Chinese consciousness-only Buddhism by obtaining all the key Indian sources and receiving direct instruction from Indian masters. Xuanzang's journey was later the subject of legend and eventually fictionalized as the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West, a major component of East Asian popular culture from Chinese opera to Japanese television (Monkey Magic).

Xuanzang spent over ten years in India traveling and studying under various Buddhist masters.[20] These masters included Śīlabhadra, the abbot of the Nālandā Mahāvihāra, who was then 106 years old.[21] Xuanzang was tutored in the Yogācāra teachings by Śīlabhadra for several years at Nālandā. Upon his return from India, Xuanzang brought with him a wagon-load of Buddhist texts, including important Yogācāra works such as the Yogācārabhūmi-śastra.[22] In total, Xuanzang had procured 657 Buddhist texts from India.[20] Upon his return to China, he was given government support and many assistants for the purpose of translating these texts into Chinese.

As an important contribution to East Asian Yogācāra, Xuanzang composed the treatise Cheng Weishi Lun, or "Discourse on the Establishment of Consciousness Only."[23] This work is framed around Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā-vijñaptimātratā ("Thirty Verses on Consciousness Only") but it draws on numerous other sources and Indian commentaries to Vasubandhu's verses to create a doctrinal summa of Indian consciousness only thought.[23] This work was composed at the behest of Xuanzang's disciple Kuiji, and became a central representation of East Asian Yogācāra.[23] Xuanzang also promoted devotional meditative practices toward Maitreya Bodhisattva.

Xuanzang's disciple Kuiji wrote a number of important commentaries on the Yogācāra texts and further developed the influence of this doctrine in China, and was recognized by later adherents as the first true patriarch of the school.[24] His Cheng weishi lun shuji (成唯識 論述記; Taishō no. 1830, vol. 43, 229a-606c) is a particularly important text for the Weishi school.[25]

After Xuanzang, the second patriarch of the Weishi school was Hui Zhao. According to A.C. Muller "Hui Zhao 惠沼 (650-714), the second patriarch, and Zhi Zhou 智周 (668-723), the third patriarch, wrote commentaries on the Fayuan yulin chang, the Lotus Sūtra, and the Madhyāntavibhāga; they also wrote treatises on Buddhist logic and commentaries on the Cheng weishi lun."[8] Another important figure is Yijing 義淨 (635–713), who traveled to India in imitation of Xuanzang. He translated several works of Vinaya, as well as Yogācāra commentaries by Dharmapāla on Dignāga’s Ālambana-parīkṣā and on Vasubandhu’s Viṃśikā.[26]

Wŏnch’ŭk's school and Korean Yogācāra

[edit]While the lineage of Kuiji and Hui Zhao was traditionally considered the "orthodox" tradition of Xuanzang's school, there were also other lineages of this tradition which differed in their interpretations from Kuiji's sect.[27] Perhaps the most influential heterodox group was a group of Yogācāra (Korean: Beopsang) scholars from the Korean Silla kingdom, mainly: Wŏnch’ŭk, Tojŭng, and Taehyŏn (大賢).[27]

Wŏnch’ŭk (圓測, 613–696) was a Korean student of Xuanzang as well as a disciple of the Shelun master Fachang (567–645).[28] He composed various texts, including Haesimmilgyǔng so (C. Jieshenmi jing shu), an influential commentary to the Saṃdhinirmocanasūtra which was even translated to Tibetan and is known as the "Great Chinese Commentary" to Tibetans. This work later influenced Tibetan scholars like Tsongkhapa.[28]

Wŏnch’ŭk's interpretations often differ from that of the school of Xuanzang and instead promotes ideas closer to those of the Shelun school, such as the doctrine of the "immaculate consciousness" (amalavijñāna) and the idea that the ālayavijñāna was essentially pure.[28] Due to this, Wŏnch’ŭk's work was criticized by the disciples of Kuiji.[29] Wŏnch’ŭk's tradition came to be known as the Ximing tradition (since he resided at Ximingsi monastery), and it was contrasted with Kuiji's tradition, also called the Ci'en tradition after Kuiji's monastery at Da Ci'ensi.[29]

While in China, Wŏnch’ŭk took as a disciple a Korean-born monk named Tojŭng (Chinese: 道證), who travelled to Silla in 692 and propounded and propagated Woncheuk's exegetical tradition there where it flourished. In Korea, these Beopsang teachings did not endure long as a distinct school, but its teachings were frequently included in later schools of thought and also studied by Japanese Yogācāra scholars.[22]

Another influential figure in Korean Yogācāra is Wŏnhyo (元曉 617–686). While he usually seen as a Huayan scholar, he also wrote many works on Yogācāra and according to Charles Muller "if we look at Wŏnhyo’s oeuvre as a whole, along with accounts of his life, his involvement in Yogācāra studies looms large, and in fact, in terms of sheer quantity, forms the largest portion of his work."[30] His work was influential on later Chinese figures like Fazang.[30]

Dharma characteristics vs Dharma nature debates

[edit]

With the rise of other Sinitic Mahayana schools to prominence, like Huayan and Chan, the Yogacara tradition of Xuanzang came under some doctrinal criticism.[2] Sinitic schools like Huayan were influenced by the buddha-nature and ekayana (one vehicle) teachings, especially the doctrines of the Awakening of Faith. They were thus connected with the teachings of the Dilun and Shelun schools.[31] As such, their doctrines differed in significant ways from that of the school of Xuanzang.[2]

The scholars of the Huayan school like Fazang (643–712), Chengguan (738–839), and Zongmi (780–841), critiqued the school of Xuanzang, which they termed "Faxiang-zong" (dharma-characteristics school, a term invented by Chengguan), on various points.[32][2] A key contention was that Xuanzang's school failed to understand the true Dharma-nature (Ch: fa-xin, dharmata or tathata, i.e. the buddha-nature, the one mind of the Awakening of Faith), even if they did understand the nature of dharmas (fa-xiang).[2] According to Dan Lusthaus, "This distinction became so important, that every Buddhist school originating in East Asia, including all forms of Sinitic Mahayana, viz. T' ien-t' ai, Hua-yen, Ch'an, and Pure Land, came to be considered Dharma-nature schools."[33]

The Huayan school sees the Dharma nature as dynamic and responding to conditions (of sentient beings), it also sees the Dharma nature (the buddha-nature, original enlightenment) as the basis and source of samsara and nirvana.[2] As such, Huayan scholars like Zongmi critiqued the view of the Xuanzang "Faxiang" school which held that the Dharma nature (suchness) was "totally inert" and "unchanging" in favor of the view found in the Awakening of Faith which sees the one mind (the dharma nature) as having both an unconditioned and a conditioned aspect. This conditioned aspect of the dharma nature is an active and dynamic aspect out of which all pure and impure dharmas arise.[32] As Imre Hamar explains:

The issue at stake is the relationship between the Absolute and phenomena. Is the tathata, the Absolute, dependent arising, or is it immovable? Does the Absolute have anything to do with the phenomenal world? According to the interpretation of the final teaching of Mahayana (i.e. Faxingzong), the Absolute and phenomena can be described with the 'water and wave' metaphor. Due to the wind of ignorance, waves of phenomena rise and fall, yet they are not different in essence from the water of the Absolute. In contrast with this explanation, the elementary teaching of Mahayana (i.e. Faxiangzong) can be presented by the metaphor of 'house and ground' . The ground supports the house but is different from it.[2]

Another key distinction and point of debate was the nature of the alayavijñana. For Xuanzang's school, the alayavijñana is a defiled consciousness, while the so called "Dharma-nature" position (following the Awakening of Faith) is that the alaya has a pure untainted aspect (which is buddha-nature) as well as an impure aspect.[2]

The schools which were more aligned with the "Dharma-nature" position (like Huayan, Tiantai and Chan) also affirmed the ultimate truth of the one vehicle, while the Xuanzang school affirms the difference among the three vehicles.[2] They also reject Xuanzang's view that states that there is a certain class of very deluded beings called icchantikas who can never become Buddhas.[2] The Xuanzang school also maintained the Five Natures Doctrine (Chinese: 五性各別; pinyin: wǔxìng gèbié; Wade–Giles: wu-hsing ko-pieh) which was seen as provisional and as being superseded by the one vehicle teaching by schools like Huayan and Tiantai.

Later history

[edit]

After the third patriarch, the influence of the school of Xuanzang declined, though it continued to be studied at certain key centers, such as Chang’an, Mt. Wutai, Zhendingfu (now) Shijiazhuang), and Hangzhou.[35] The Weishi (consciousness-only) school survived into the Song and Yuan dynasties, but as a minor school with little influence.[35] However its texts have remained important sources for the study of Yogācāra thought down to today.[8][35]

The Xuanzang school's influence declined due to competition with other Chinese Buddhist traditions such as Tiantai, Huayan, Chan and Pure Land Buddhism. Nevertheless, classic Yogācāra philosophy continued to exert an influence, and Chinese Buddhists of other schools relied on its teachings to enrich their own intellectual traditions.[22][36]

An important later figure associated with Yogācāra studies was the syncretic Chan scholar monk Yongming Yanshou (904–975), who wrote some commentaries on Yogācāra texts.[37] During the Ming dynasty, two scholars also wrote Weishi commentaries: Mingyu 明昱 (1527–1616) and Zhixu 智旭 (1599–1655).[38]

Other Yogācāra teachings remained popular in Chinese Buddhism, such as devotion to the bodhisattva Maitreya (who was associated with the tradition and is seen as the founder of Yogācāra). Various later Chinese figures promoted Maitreya devotion as a Pure Land practice and as a way to receive teachings in visions.[34] Hanshan Deqing (1546–1623) was one figure who describes a vision of Maitreya.[39]

Modern revival

[edit]

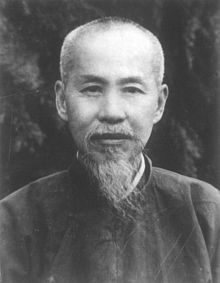

The 20th century saw a revival in Weishi studies in China.[40] Important figures in this revival include Yang Wenhui (1837-1911), Taixu, Liang Shuming, Ouyang Jingwu (1870–1943), Wang Xiaoxu (1875-1948), and Lu Cheng.[41][42][43][44] Weishi studies was also revived among Japanese philosophers like Inoue Enryō.[42]

Modern Chinese thinkers of the Weishi studies revival also discussed Western philosophy (especially Hegelian and Kantian thought) and modern science in terms of Yogacara thought.[42][45]

In his 1929 book on the history of Chinese Buddhism, Jiang Weiqiao wrote:

In modern times, there are few śramaṇa who research [Faxiang]. Various laypeople, however, take this field of study to be rigorous, systematic and clear, and close to science. For this reason, there are now many people researching it. Preeminent among those writing on the topic are those at Nanjing's Inner Studies Academy, headed by Ouyang Jian.[46]

Ouyang Jian founded the Chinese Institute of Inner Studies (Chinese: 支那內學院), which provided education in Yogācāra teachings and the Prajñāparamita sūtras, given to both monastics and laypeople.[47] Many modern Chinese Buddhist scholars are second-generation descendants of this school or have been influenced by it indirectly.[47]

New Confucian thinkers also participated in the revival of Weishi studies.[41][48][42] New Confucians like Xiong Shili, Ma Yifu, Tang Junyi and Mou Zongsan, were influenced by the philosophy of Indian Yogācāra philosophy, and by the thought of the Awakening of Faith, though their work also critiqued and modified Weishi philosophy in various ways.[49][50]

The work of Xiong Shili was particularly influential in the establishment of what is now called New Confucianism. His A New Treatise on Vijñaptimātra (新唯識論, Xin Weishi Lun) draws on Yogacara and Confucian thought to construct a new philosophical system.[51]

History in Japan

[edit]

Early period

[edit]The Consciousness-Only teachings were transmitted to Japan as "Hossō-shū" (法相宗, Japanese for "Faxiang School"), and they made considerable impact.[52] There were various key figures who established early Hossō in Japan. One of them was Dōshō 道昭 (629–749), a student of Xuanzang from 653 to 660. Dōshō and his students Gyōki and Dōga followed the "orthodox" texts and teachings of Xuanzang's school and transmitted these to Japan at Gangōji Temple.[53] Other important figures who also studied under Xuanzang were Chitsu and Chitatsu. Together with Dōshō they defended the orthodox interpretations of Kuiji.[53]

Another line of transmission was that of Chihō, Chiran, and Chiyu (all three visited Korea and then China c. 703), as well as the later figures Gien / Giin (653-728) and Genbō (d. 746). This tradition is known as the "Northern Temple transmission" since the lineage came to be based at Kōfuku-ji.[54] This tradition was known to follow the teachings of the school of the Korean monk Wŏnch’ŭk in contrast to the "southern temple" tradition of Gangōji.[54]

The northern and southern temple traditions debated each other for centuries over their varying interpretations (Kuiji's "orthodoxy" vs the views of the Silla Korean masters and their commentaries).[55] These debates can be found in various later Hossō doctrinal sources, including: Record of the Light of the Lamp of Hossō (Hossō tōmyō ki 法相燈明記; 815) by Zen’an, Summary of the School of the Weishi lun (Yuishikiron dōgakushō 唯識論同學鈔) by Ryōsan 良算 (1202–?) and Chapters Providing a Brief Study of the Mahāyāna Yogācāra (Daijō hossō kenjinshō 大乘法相硏神章序) by Gomyō (750–834).[55]

Hossō was an influential school during the Heian period. Hossō scholars also frequently debated with other emerging schools of Japanese Buddhism at the time. Both the founder of Shingon, Kūkai, and the founder of Tendai, Saichō, exchanged letters of debate with Hossō scholar Tokuitsu.[56] Saichō condemned the school for not accepting the one vehicle teaching of the Lotus Sutra, which was seen as a provisional teaching in Hossō. Kukai, who became an influential figure at Nara, was more conciliatory with Hossō, and maintained amicable relations with the tradition. After Kukai, Shingon scholar monks often studied and commented on Hossō sources, while Hossō monks adopted Shingon ritual practices.[57] However, over time, the universalist doctrine of the Tendai school won out and the Hossō position (which held that only some beings can become Buddhas and some beings called icchantikas have no hope for awakening) became a marginal view.[57]

Kamakura revival and modernity

[edit]

The tumultuous Kamakura period (1185–1333), saw a revival (fukkō) and reform (kaikaku) of Hossō school teachings, which was led by figures like Jōkei (1155–1213) and Ryōhen.[58] The reformed doctrines can be found in key sources like Jō yuishiki ron dōgaku shō (A Collaborative Study of the Treatise on Consciousness-only), Jōkei's Hossōshū shoshin ryakuō and Ryōhen's Kanjin kakumushō (Summation on Contemplating the Mind and Awakening from a Dream).[58] A key element of Jōkei's teachings is the idea that even though the five classes of beings and the one vehicle teaching are relatively true, they are not ultimately so (since all phenomena are ultimately empty, non-dual and "neither the same nor different"). He also affirms that even icchantikas can attain enlightenment, since they will never be abandoned by the Buddhas and their compassionate power (which is not bound by causal laws).[58]

In a similar fashion, Ryōhen writes:

Thus it should be remembered that in our school the doctrine of one vehicle and the doctrine of five groups of sentient beings are regarded as being equally true, for the doctrine of one vehicle is formulated from the standpoint that recognizes the unchangeable quality of the underlying substance of dharrnas, whereas the doctrine of the five groups of sentient beings has its roots in the distinctiveness of conditioned phenomena.… Thus, since our standpoint is that the relationship between the absolute and conditioned phenomena is one of “neither identity nor difference,” both the concept of one vehicle as well as the concept of five groups of sentient beings are equally valid.[58]

During the Kamakura, several new Buddhist schools were founded, with the various Pure Land sects derived from Hōnen becoming especially popular. As a novice monk, Hōnen had studied with Hossō scholars, but he later debated them while promoting his Pure land path.[59] Jōkei was among Hōnen's toughest critics.[60]

Jōkei is also known for popularizing the devotional aspects of Hossō, and for working to make it accessible to a wider audience.[60][61] Jōkei promoted devotion to various figures, like Shakyamuni, Kannon, Jizo, and Maitreya, as well as numerous practices, like various nenbustu seeking birth in a pure land, dharani, precepts, liturgy (koshiki), rituals, lectures, worship of relics, etc.[61] His pluralist and eclectic teachings thus offer a contrast to the more exclusive Kamakura schools who focused on one Buddha (Amitabha) or one practice (nembutsu etc.). For Jōkei, difference and diversity matters and people are not all the same (on the relative level), and thus it is not true that one practice or one Buddha is suitable for everyone.[61] However, like the Pure Land schools, Jōkei stressed the importance of relying on the "other power" (of a Buddha or bodhisattva) and of birth in a pure land (Jōkei stressed the pure land of Maitreya), as well as practices that were accessible to less elite practitioners.[61]

Jōkei is also a leading figure in the efforts to revive monastic discipline at places like Tōshōdai-ji, Kōfuku-ji and counted other notable monks among his disciples, including Eison, who founded the Shingon Risshu sect.[62]

Although a relatively small Hossō sect exists in Japan to this day, its influence diminished due to competition from newer Japanese Buddhist schools like Zen and Pure Land.[22] During the Meiji period, as tourism became more common, the Hossō sect was the owner of several famous temples, notably Hōryū-ji and Kiyomizu-dera. However, as the Hossō sect had ceased Buddhist study centuries prior, the head priests were not content with giving part of their tourism income to the sect's organization. Following the end of World War II, the owners of these popular temples broke away from the Hossō sect, in 1950 and 1965, respectively. The sect still maintains Kōfuku-ji and Yakushi-ji.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Siderits, Mark, Buddhism as philosophy, 2017, p. 146.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hamar, Imre, 2007. “A Huayan Paradigm for the Classification of Mahāyāna Teachings: The Origin and Meaning of Faxingzong and Faxiangzong.” In Imre Hamar, ed. Reflecting Mirrors: Perspectives on Huayan Buddhism. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 195–220.

- ^ Sheng-yen 2007, p. 13.

- ^ Tagawa 2014, p. 1–10.

- ^ Schmithausen, Lambert. 1987. Ālayavijñāna: On the Origin and the Early Development of a Central Concept of Yogâcāra Philosophy. Tokyo: International Institute for Buddhist Studies. Studia Philologica Buddhica Monograph Series. IV

- ^ Paul 1984, p. 6.

- ^ Makeham, John. Transforming Consciousness: Yogacara Thought in Modern China, p. 4. Oxford University Press, 2014

- ^ a b c d e Muller, A.C. "Quick Overview of the Faxiang School 法相宗". www.acmuller.net. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ^ King Pong Chiu (2016). Thomé H. Fang, Tang Junyi and Huayan Thought: A Confucian Appropriation of Buddhist Ideas in Response to Scientism in Twentieth-Century China, p. 53. BRILL.

- ^ a b c Makeham, John. Transforming Consciousness: Yogacara Thought in Modern China, p. 6. Oxford University Press, 2014

- ^ Jorgensen, John; Lusthaus, Dan; Makeham, John; Strange, Mark, trans. (2019), Treatise on Awakening Mahāyāna Faith, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, in Introduction (pp. 1–10).

- ^ Brunnhölzl, Karl (2015). When the Clouds Part: The Uttaratantra and Its Meditative Tradition as a Bridge between Sutra and Tantra, p. 94. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-0-8348-3010-3

- ^ Kantor, Hans-Rudolf. "Philosophical Aspects of Sixth-Century Chinese Buddhist Debates on “Mind and Consciousness”", pp. 337–395 in: Chen-kuo Lin / Michael Radich (eds.) A Distant Mirror Articulating Indic Ideas in Sixth and Seventh Century Chinese Buddhism. Hamburg Buddhist Studies, 3 Hamburg: Hamburg University Press 2014.

- ^ Muller, Charles. 地論宗 School of the Treatise on the Bhūmis (2017), Digital Dictionary of Buddhism. http://www.buddhism-dict.net

- ^ a b Paul 1984, p. 32-33.

- ^ Keng Ching and Michael Radich. "Paramārtha." Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Volume II: Lives, edited by Jonathan A. Silk (editor-in chief), Richard Bowring, Vincent Eltschinger, and Michael Radich, 752-758. Leiden, Brill, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Radich, Michael. The Doctrine of *Amalavijnana in Paramartha (499-569), and Later Authors to Approximately 800 C.E. Zinbun 41:45-174 (2009) Copy BIBTEX

- ^ "amalavijñāna - Buddha-Nature". buddhanature.tsadra.org. Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- ^ Lusthaus, Dan (1998), Buddhist Philosophy, Chinese. In: Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, p. 84. Taylor & Francis.

- ^ a b c Liu 2006, p. 220.

- ^ Wei Tat. Cheng Weishi Lun. 1973. p. li

- ^ a b c d Tagawa 2014, p. xx-xxi.

- ^ a b c Liu 2006, p. 221.

- ^ Buswell & Lopez 2013, p. 283-4.

- ^ Lusthaus, Dan (undated). Quick Overview of the Faxiang School (法相宗). Source: [1] (accessed: December 12, 2007)

- ^ Makeham, John. Transforming Consciousness: Yogacara Thought in Modern China, p. 9. Oxford University Press, 2014

- ^ a b Moro, Shigeki (2020). "Sthiramati, Paramārtha, and Wŏnhyo: On the Sources of Wŏnhyo's Chungbyŏn punbyŏllon so". Journal of Korean Religions. 11 (1): 23–43. doi:10.1353/jkr.2020.0000.

- ^ a b c Wŏnch’ŭk in The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, 996–97. Princeton University Press, 2014.

- ^ a b Buswell, Robert E. (2004). Encyclopedia of Buddhism, 'Wŏnch'ŭk', p. 903. Volumes 1,2. Macmillan Reference.

- ^ a b Muller, A. Charles. "Introduction: Yogācāra Studies of Silla." Journal of Korean Religions Vol. 11, No. 1 (April 2020): 5–21 6 2020 Institute for the Study of Religion, Sogang University, Korea.

- ^ King Pong Chiu (2016). Thomé H. Fang, Tang Junyi and Huayan Thought: A Confucian Appropriation of Buddhist Ideas in Response to Scientism in Twentieth-Century China, p. 53. BRILL.

- ^ a b Gregory, Peter N. Tsung-mi and the Sinification of Buddhism, p. 189. University of Hawaii Press, 2002.

- ^ Lusthaus, Dan. Buddhist Phenomenology: A Philosophical Investigation of Yogacara Buddhism and the Ch ' eng Wei-shih lun, p. 372. London: Routledge Curzon, 2002.

- ^ a b Jingjing Li (2018). "Traversing China for the Forgotten Pure Land of Maitreya Buddha". Buddhistdoor Global. Retrieved 2024-02-07.

- ^ a b c Makeham, John. Transforming Consciousness: Yogacara Thought in Modern China, p. 10. Oxford University Press, 2014

- ^ Makeham, John. Transforming Consciousness: Yogacara Thought in Modern China, p. 9. Oxford University Press, 2014

- ^ Makeham, John. Transforming Consciousness: Yogacara Thought in Modern China, pp. 10-11. Oxford University Press, 2014

- ^ Makeham, John. Transforming Consciousness: Yogacara Thought in Modern China, p. 11. Oxford University Press, 2014

- ^ Hanshan Deqing 1995.

- ^ Makeham, John. Transforming Consciousness: Yogacara Thought in Modern China, pp. 13-14. Oxford University Press, 2014

- ^ a b Makeham, John. Transforming Consciousness: Yogacara Thought in Modern China, Oxford University Press, 2014

- ^ a b c d Hammerstrom, Erik J.. “The Expression "The Myriad Dharmas are Only Consciousness" in Early 20th Century Chinese Buddhism.” (2010).

- ^ Nan 1997, p. 42.

- ^ Sheng-yen 2007, p. 217.

- ^ Makeham, John. Transforming Consciousness: Yogacara Thought in Modern China, p. 1. Oxford University Press, 2014

- ^ Hammerstrom, Erik J. (2010). "The Expression "The Myriad Dharmas are Only Consciousness" in Early 20th Century Chinese Buddhism" (PDF). Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal 中華佛學學報. 23: 73. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-04-09. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- ^ a b Nan 1997, p. 141.

- ^ Aviv, E. (2020). "Chapter 3 The Debate over the Awakening of Faith in Mahāyāna". In Differentiating the Pearl from the Fish-Eye. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004437913_005

- ^ Makeham, John. The Awakening of Faith and New Confucian Philosophy, Brill, 2021, introduction.

- ^ Makeham, John. Transforming Consciousness: Yogacara Thought in Modern China, p. 30. Oxford University Press, 2014.

- ^ Muller, A.C. Xiong Shili and the New Treatise: A review discussion of Xiong Shili, New Treatise on the Uniqueness of Consciousness, an annotated translation by John Makeham. SOPHIA 56, 523–526 (2017). doi:10.1007/s11841-017-0595-8

- ^ Sho, Kyodai (2002). The Elementary-Level Textbook: Part 1: Gosho Study "Letter To The Brothers". SGI-USA Study Curriculum. Source: "Elementary Study - Letter to the Brothers". Archived from the original on 2007-12-15. Retrieved 2008-01-07. (accessed: January 8, 2007)

- ^ a b Green, Ronald S. Chanju Mun. Gyōnen’s Transmission of the Buddha Dharma in Three Countries, pp. 59-60. BRILL, 2018.

- ^ a b Green, Ronald S. Chanju Mun. Gyōnen’s Transmission of the Buddha Dharma in Three Countries, pp. 60-62. BRILL, 2018.

- ^ a b Green, Ronald S. (2020). Early Japanese Hosso in Relation to Silla Yogacara in Disputes between Nara's Northern and Southern Temple Traditions. Journal of Korean Religions, 11(1), 97–121. doi:10.1353/jkr.2020.0003

- ^ Abe 1999, p. 208–19.

- ^ a b Ford, James L. (2006). Jokei and Buddhist Devotion in Early Medieval Japan. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 35-68. ISBN 978-0-19-518814-1

- ^ a b c d Ford, James L. (2006). Jokei and Buddhist Devotion in Early Medieval Japan. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 35-68. ISBN 978-0-19-518814-1

- ^ "JODO SHU English". www.jodo.org. Archived from the original on 2013-10-31. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ^ a b Ford 2006b, p. 110–113.

- ^ a b c d Ford, James L. (2006). Jokei and Buddhist Devotion in Early Medieval Japan. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 69-71. ISBN 978-0-19-518814-1

- ^ Ford 2006a, p. 132–134.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abe, Ryūichi (1999). The Weaving of Mantra: Kūkai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-52887-0.

- Buswell, Robert; Lopez, Donald S. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3.

- Ford, James L. (2006a). Jōkei and Buddhist Devotion in Early Medieval Japan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-972004-0.

- Ford, James (18 April 2006b). "Buddhist Ceremonials (Kōshiki) and the Ideological Discourse of Established Buddhism in Medieval Japan". In Payne, Richard K.; Leighton, Taigen Dan (eds.). Discourse and Ideology in Medieval Japanese Buddhism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-24209-2.

- Hamar, Imre (2007). Reflecting Mirrors: Perspectives on Huayan Buddhism. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05509-3.

- Hanshan Deqing (1995). The Autobiography & Maxims of Master Han Shan. H.K. Buddhist Book.

- Liu, JeeLoo (2006). An Introduction to Chinese Philosophy: From Ancient Philosophy to Chinese Buddhism. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4051-2949-7.

- Minagawa, Sachiyoshi (1998). "Medieval Japanese Vijnaptimatra Thought-On nyakunmuro". Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies. 46 (2).

- Nan, Huaijin (1997). Basic Buddhism: Exploring Buddhism and Zen. Weiser Books. ISBN 978-1-57863-020-2.

- Paul, Diana Y. (1984). Philosophy of Mind in Sixth-century China: Paramārtha's "evolution of Consciousness". Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1187-6.

- Puggioni, Tonino (2003). "The Yogacara-faxiang faith and the Korean Beopsang [法相] tradition" (PDF). Seoul Journal of Korean Studies. 16: 75–112. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-14.

- Sheng-yen (2007). Orthodox Chinese Buddhism: A Contemporary Chan Master's Answers to Common Questions. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-55643-657-4.

- Tagawa, Shun'ei (2014). Living Yogacara: An Introduction to Consciousness-Only Buddhism. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-86171-895-5.

- Yoshimura, Hiromi (2006). "Plural Theories on Vijnaptimatra in the Mahayanasutralamkara". Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies. 54 (2).