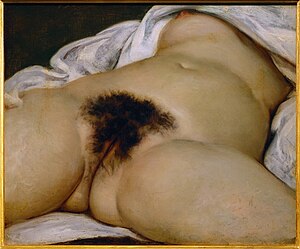

L'Origine du monde

| L'Origine du monde | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Gustave Courbet |

| Year | 1866 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 46 cm × 55 cm (18 in × 22 in) |

| Location | Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

L'Origine du monde ("The Origin of the World") is a picture painted in oil on canvas by the French painter Gustave Courbet in 1866. It is a close-up view of the vulva and abdomen of a naked woman, lying on a bed with legs spread.

History

[edit]Identity of the model

[edit]

Art historians have speculated for years that Courbet's model for L'Origine du monde was his favourite model, Joanna Hiffernan, also known as Jo. Her lover at the time was the American painter James Whistler, a friend of Courbet.[1]

Hiffernan was the subject of a series of four portraits by Courbet titled Jo, la belle Irlandaise (Jo, the beautiful Irishwoman) painted in 1865–66. The possibility that she was the model for L'Origine du monde[2][3] or that she was having an affair with Courbet might explain Courbet's and Whistler's brutal separation a short while later.[4] In spite of Hiffernan's red hair contrasting with the darker pubic hair of L'Origine du monde, the hypothesis continues that Hiffernan was the model. Redhead Jacky Colliss Harvey puts forward the idea that the woman's body hair suggests a more obvious candidate might be the brunette painted with Hiffernan in Courbet's Le Sommeil; and that the identification with Hiffernan has been greatly influenced by the eroticised and sexualised image of the female redhead.[5]

In February 2013, Paris Match reported that Courbet expert Jean-Jacques Fernier had authenticated a painting of a young woman's head and shoulders as the upper section of L'Origine du monde which according to some was severed from the original work. Fernier has stated that because of the conclusions reached after two years of analysis, the head will be added to the next edition of the Courbet catalogue raisonné.[2][6] The Musée d'Orsay has indicated that L'Origine du monde was not part of a larger work.[7] The Daily Telegraph reported that "experts at the [French] art research centre CARAA (Centre d'Analyses et de Recherche en Art et Archéologie) were able to align the two paintings via grooves made by the original wooden frame and lines in the canvas itself, whose grain matched."[2] According to CARAA, it performed pigment analyses which were identified as classical pigments of the 2nd half of the 19th century. No other conclusions were reported by the CARAA.[8] The claim reported by Paris Match was characterized as dubious by Le Monde art critic Philippe Dagen, indicating differences in style, and that canvas similarities could be caused by buying from the same shop.[9]

Documentary evidence however links the painting with Constance Quéniaux, a former dancer at the Paris Opera and a mistress of the Ottoman diplomat Halil Şerif Pasha (Khalil Bey) who commissioned the painting.[10] According to the historian Claude Schopp and the head of the French National Library's prints department, Sylvie Aubenas, the evidence is found in correspondence between Alexandre Dumas fils and George Sand.[11] Another potential model was Marie-Anne Detourbay, who also was a mistress of Halil Şerif Pasha.[11]

Owners

[edit]Halil Şerif Pasha (Khalil Bey), an Ottoman diplomat, is believed to have commissioned the work shortly after he moved to Paris. Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve introduced him to Courbet and he ordered a painting to add to his personal collection of erotic pictures, which already included Le Bain turc (The Turkish Bath) from Ingres and another painting by Courbet, Le Sommeil (The Sleepers), for which it is supposed that Hiffernan was one of the models.[10]

After Khalil Bey's finances were ruined by gambling, the painting subsequently passed through a series of private collections. It was first bought during the sale of the Khalil Bey collection in 1868, by antique dealer Antoine de la Narde. Edmond de Goncourt hit upon it in an antique shop in 1889, hidden behind a wooden pane decorated with the painting of a castle or a church in a snowy landscape. According to Robert Fernier, who published two volumes of the Courbet catalogue raisonné and founded the Musée Courbet, Hungarian collector Baron Ferenc Hatvany bought it at the Bernheim-Jeune gallery in 1910 and took it with him to Budapest. Towards the end of the Second World War the painting was looted by Soviet troops, but later ransomed by Hatvany. Hatvany left Hungary, which was on the brink of a Communist takeover, in 1947. He was allowed to take only one art work with him, and he took L'Origine to Paris.[12]

In 1955 L'Origine du monde was sold at auction for 1.5 million francs, about US$4,285 at the time.[13] Its new owner was the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. He and his wife, actress Sylvia Bataille, installed it in their country house in Guitrancourt. Lacan asked André Masson, his stepbrother, to build a double bottom frame and draw another picture thereon. Masson painted a surrealist, allusive version of L'Origine du monde.[14][15]

The New York public had the opportunity to view L'Origine du monde in 1988 during the Courbet Reconsidered show at the Brooklyn Museum; the painting was also included in the exhibition Gustave Courbet at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2008. After Lacan died in 1981, the French Minister of Economy and Finances agreed to settle the family's inheritance tax bill through the transfer of the work ("Dation en paiement" in French law) to the Musée d'Orsay; the transfer was finalized in 1995.[10]

Provocative work

[edit]During the 19th century, the display of the nude body underwent a revolution whose main activists were Courbet and Manet. Courbet rejected academic painting and its smooth, idealised nudes, but he also directly recriminated the hypocritical social conventions of the Second Empire, where eroticism and even pornography were acceptable in mythological or oneiric paintings.

Courbet later insisted he never lied in his paintings, and his realism pushed the limits of what was considered presentable. With L'Origine du monde, he has made even more explicit the eroticism of Manet's Olympia. Maxime Du Camp, in a harsh tirade, reported his visit to the work's purchaser, and his sight of a painting "giving realism's last word".[16]

By the very nature of its realistic, graphic nudity, the painting still has the power to shock and trigger censorship.

Although moral standards and resulting taboos regarding the artistic display of nudity have changed since Courbet, owing especially to photography and cinema, the painting remained provocative. Its arrival at the Musée d'Orsay caused high excitement. According to postcard sales, in 2007 L'Origine du monde was the second most popular painting in the Musée d'Orsay, after Renoir's Bal du moulin de la Galette.[17]

Some critics maintain that the body depicted is not (as has been argued) a lively erotic portrayal of a female but of a corpse: "L'Origine does not represent a full female body but rather a slice of one, cut off by the frame [...]. The pallidness of the skin and the mortuary gauze surrounding the body suggest death."[18]

Influence

[edit]The explicitness of the picture may have served as an inspiration, albeit with a satirical twist, for Marcel Duchamp's last major work, Étant donnés (1946–1966), a construction also featuring the image of a woman lying on her back with her legs spread.[19]

In 1989, French artist Orlan created the cibachrome L'origine de la guerre (The Origin of War), a male version of L'origine du monde showing a penile erection.[20]

Brazilian artist Vik Muniz created two versions of the famous painting. "The first [1999] is a photograph made of dust or dirt, which plays with the common moralist association between female genitalia and filth. In the second piece [2013], Muniz remakes L'Origine from an assemblage of journal clippings that are reminiscent of the anatomic and artistic procedure of cutting that produced [...] the female body."[21]

Two Origins of the World (2000) by Mexican artist Enrique Chagoya "recycles L'Origine du monde as a spectral backdrop behind three solid black, blue and white squares of canvas in three of the corners of the painting. In the foreground of the bottom right corner, an indigenous man sits at a fourth canvas, this one on an easel, apparently 'interpreting' the Courbet painting."[22]

In 2002, American artist Jack Daws created an homage to the painting. Entitled Origins of the World, it is a collection of various photographs of vulvas, taken from pornographic magazines, and framed in montage.[23]

The British artist Anish Kapoor created an installation in 2004 called L'Origine du monde, which references Courbet's painting. The piece is in the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa in Japan.[24]

The image is also referenced as inspiring Catherine Breillat's filming of the female genitalia in her 2004 film Anatomie de l'enfer (Anatomy of Hell).[25]

The Serbian performance artist Tanja Ostojić parodied the work in a poster in 2005, informally called the "EU panties" poster. Like Courbet's painting, the poster proved controversial, and was ultimately removed from the art exhibition in which it was originally displayed.[26]

The French artist Bettina Rheims closes The Book of Olga (2008) with a photo of protagonist Olga Rodionova depicting L'Origine du monde almost completely. The few differences represent the evolution of tastes from the 19th to the 21st centuries: perfectly depilated genitalia with clitoral piercing jewelry and an intimate tattoo of Olga Rodionova, in comparison to the natural hairy look of Constance Quéniaux.[27] The controversial book gained wide fame and became the subject of a legal fight in Russia.

On 23 February 2009 in Braga, Portugal, the police confiscated the book Pornocratie by Catherine Breillat, displayed in bookshops using L'Origine du monde as its cover.[28] A great deal of controversy was sparked by the police action. The reason given was the need to maintain public order. Also, the book title incorrectly hinted at pornographic content; Portuguese law forbids public displays of pornography.[citation needed]

In 2010, British composer Tony Hymas composed De l'origine du monde a musical suite dedicated to the picture as well as relations between Courbet and the Paris Commune, based on texts by Courbet himself, Charles Baudelaire and Pierre Dupont.[citation needed]

The German-born Turkish artist Taner Ceylan painted a work named 1879 (From the Lost Paintings Series) (2011) in which a veiled Ottoman noblewoman stands before the framed canvas of L'Origine du monde.[29][30]

On 29 May 2014, a Luxembourg performance artist, Deborah De Robertis, sat on the floor in front of the painting and mimicked the view of the subject. This resulted in security guards closing the room and her arrest.[31][32]

US artist Candice Lin recreated L'Origine du monde with an audiovisual sculpture, Hunter Moon / Inside Out (2015). In it, Courbet's L'Origine du monde with eyes "looks back at the onlookers." From a feminist point of view, Lin's work challenges "the asymmetry of power [...] between those who look and those who are seen."[33]

In May 2024 the painting was one of five painted with "Me Too" at the Centre Pompidou-Metz by two women in a performance art stunt organised by Deborah De Robertis[34][35] in protest of predatory and exploitative behavior by exhibition curator Bernard Marcadé and other men in the art world.[36][37]

In October 2024, in her book "The Underside of the Origin of the World", Giselle Blanchard shows that the attribution of the painting to Courbet is an axiom, a truth that seems so self-evident that it would be useless to demonstrate it. In an original conjecture, in the form of a detective novel, the author puts forward arguments suggesting that another great figure of realistic art could be at the origin of "The Origin of the World". Giselle Blanchard, “The underside of the Origin of the World”, Editions du Palio, 2024, ISBN 9782354491321

Censorship and legal battles

[edit]In February 1994, the novel Adorations perpétuelles (Perpetual Adorations) by Jacques Henric reproduced L'Origine du monde on its cover. Police visited several French bookshops to have them withdraw the book from their windows. A few proprietors maintained the book, but others complied, and some voluntarily removed it.[citation needed]

In February 2011, Facebook censored L'Origine du monde after it was posted by Copenhagen-based artist Frode Steinicke, to illustrate his comments about a television program aired on DR2. Following the incident, many other Facebook users defiantly changed their profile pictures to the Courbet painting in an act of solidarity with Steinicke. Facebook, which originally disabled Steinicke's profile, finally re-enabled it without the L'Origine du monde picture. As the case won media attention, Facebook deleted other pages about the painting.[38][39]

In October 2011, again, a complaint was lodged against Facebook with the Tribunal de grande instance de Paris (Paris court of general jurisdiction) by a French Facebook user after his profile was disabled for showing a picture of L'Origine du monde. The picture was a link to a television program aired on Arte about the history of the painting. As he got no answer to his emails to Facebook, he decided to lodge a complaint for "infringement of freedom of expression" and against the legality of Facebook's terms which define the courts located in Santa Clara County, California, as the exclusive place of jurisdiction for all litigating claims.[40] In February 2016, the Paris court ruled that Facebook could be sued in France.[41]

In 2018 the French court ruled that Facebook had been wrong to close his account. Facebook has changed its policies to allow naked images in art works, and made a donation to a French street art association.[42][43][44]

Filmography

[edit]- Jean Paul Fargier, L'Origine du monde, 1996, 26 minutes[45]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Jones, Jonathan (25 September 2018). "Who posed for the 'Mona Lisa of vaginas'?". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ a b c Henry Samuel (7 February 2013). "Amateur art buff finds £35 million head of Courbet masterpiece". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Noël, Benoit; Hournon, Jean (2006). "Gustave Courbet – L'Origine du Monde, 1866". Parisiana – La capitale des peintres au XIXème siècle (in French). Les Presses Franciliennes. p. 37. ISBN 9782952721400.

- ^ Dorothy M. Kosinski (1988). "Gustave Courbet's The Sleepers The Lesbian Image in Nineteenth Century French Art and Literature". Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 9, No. 18, p.187

- ^ Colliss Harvey, Jacky (2015). RED: A History of the Redhead. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal. pp. 119–120. ISBN 978-1-57912-996-5.

- ^ "L'Origine du monde: Le secret de la femme cachée". Paris Match (in French). 7 February 2013. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ "Has the head of The Origin of the World been found?". The Telegraph. 10 February 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ "Summary of analytical report – Painting on canvas, portrait of a woman" Archived 2015-02-17 at the Wayback Machine, Centre d'Analyses et de Recherche en Art et Archéologie, 7 February 2013

- ^ Ruadhán Mac Cormaic (9 February 2013). "Art collector claims to have found top part of Courbet's Origin of the World". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Dickey, Christopher (31 December 2018). "The Muslim Playboy Behind Paris' Most Scandalous Painting". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Mystery solved? Identity of Courbet's 19th-century nude revealed". the Guardian. Paris. Agence France-Presse. 25 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ Konstantin Akinsha (1 February 2008). "The Mysterious Journey of an Erotic Masterpiece". ARTnews.

- ^ "Measuring Worth – Relative Worth Comparators and Data Sets". www.measuringworth.com.

- ^ Lacan and the Matter of Origins by Shuli Barzilai, p. 8

- ^ "courbet – origin of the world". www.lacan.com.

- ^ Du Camp 1878, p. 190.

- ^ Hutchinson, Mark (8 August 2007). "The history of The Origin of the World". The Times Literary Supplement. London.

- ^ Uparella & Jauregui 2018, p. 95.

- ^ "Femalic Molds", The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal (toutfait.com), 1 April 2003/5 May 2016

- ^ "ORLAN: L'origine de la Guerre". The Eye of Photography. 21 December 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ Uparella & Jauregui 2018, pp. 103–105.

- ^ Uparella & Jauregui 2018, p. 105.

- ^ "Jack Daws Sculpture". Greg Kucera Gallery, Inc. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ "金沢21世紀美術館". 金沢21世紀美術館.

- ^ "Catherine Breillat, cinéaste" Archived 2009-10-04 at the Portuguese Web Archive, interview by Laurent Devanne, Radio libertaire (1 February 2004)

- ^ Dickinson, Bob (April 2016). "A Bridge Too Far". Art Monthly (395): 3. ISSN 0142-6702. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Bettina Rheims. The Book of Olga (Limited ed.). Taschen.

- ^ Lusa (23 February 2009). "PSP apreende livros por considerar pornográfica capa com quadro de Courbet" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 25 May 2009. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- ^ Harris, Garreth (12 September 2014). "Up front and personal: Turkish artist Taner Ceylan". Financial Times. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "Taner Ceylan 1879 (FROM THE LOST PAINTING SERIES)". Sothebys. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Uparella & Jauregui 2018, pp. 82–83.

- ^ "An artist has been arrested (again) for a nude stunt in a Paris gallery". Independent.co.uk. 18 January 2016.

- ^ Uparella & Jauregui 2018, p. 85.

- ^ "Painting of vagina by French artist Gustave Courbet sprayed with 'MeToo' graffiti". The Guardian. 7 May 2024.

- ^ Gareth Harris (7 May 2024). "Courbet's 'The Origin of the World' daubed with Me Too at Centre Pompidou-Metz". The Art Newspaper.

- ^ "2 women charged with spraying MeToo graffiti on nude painting at Paris museum". 11 May 2024.

- ^ "Instagram".

- ^ Emily Greenberg "Facebook, Censorship and Art" Archived 2011-11-05 at the Wayback Machine, Cornell Daily Sun, 8 March 2011

- ^ Dépêche AFP du 17/02/10 "L'Origine du monde de Courbet interdit de Facebook pour cause de nudité"

- ^ "L'Origine du monde assigne Facebook en justice", Le Point, 24 October 2011

- ^ "Facebook in landmark censorship case after banning user who posted naked artwork". The Independent. 13 February 2016.

- ^ "Facebook finally settles censorship dispute over Courbet 'vagina painting'". Dazed. 6 August 2019.

- ^ Harris, Gareth (6 August 2019). "Long-running Facebook battle over censored Courbet painting gets happy ending". The Art Newspaper.

- ^ Stapley-Brown, Victoria (16 March 2018). "French court makes mixed ruling in Courbet 'censorship' case". The Art Newspaper.

- ^ "Documentaire de Jean-Paul Fargier" (in French). arte tv. 2 November 2007. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 14 July 2008.

Sources

[edit]- Dagen, Philippe (21 June 1995). "Le Musée d'Orsay dévoile L'Origine du monde". Le Monde.

- Dagen, Philippe (22 October 1996). "Sexe, peinture et secret". Le Monde.

- Du Camp, Maxime (1878). Les Convulsions de Paris (in French). Vol. II: Épisodes de la Commune. Paris: Hachette.

- Lechien, Isabelle Enaud. James Whistler. ACR Édition.

- Guégan, Stéphane; Michèle Haddad. L'ABCdaire de Courbet. Flammarion.

- Noiville, Florence (25 March 1994). "Le retour du puritanisme". Le Monde.

- Savatier, Thierry (2006). L'Origine du monde, histoire d'un tableau de Gustave Courbet. Paris: Bartillat.

- Schlesser, Thomas (2005). "L'Origine du monde". Dictionnaire de la pornographie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Teyssèdre, Bernard (1996). Le roman de l'Origine. Paris: Gallimard.

- Uparella, Paola; Jauregui, Carlos A. (2018). "The Vagina and the Eye of Power (Essay on Genitalia and Visual Sovereignty)". H-Art. 3 (3): 79–114. doi:10.25025/hart03.2018.04.

External links

[edit]- Musée d'Orsay: L'Origine du monde Archived 19 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- Musée d'Orsay: L'Origine du monde (in French)

- Musée d'Orsay: L'Origine du monde – Notice d´Oeuvre (in French)

- News from CARAA (in French)

- Conference from Musée d'Orsay (in French)

- Composition Archived 5 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine of L'Origine du monde

- 2018 BBC story