London School of Economics

| |||||||||||||

| Motto | Latin: Rerum cognoscere causas | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Motto in English | To understand the causes of things | ||||||||||||

| Type | Public research university | ||||||||||||

| Established | 1895 | ||||||||||||

| Endowment | £255.5 million (2024)[1] | ||||||||||||

| Budget | £525.6 million (2023/24)[1] | ||||||||||||

| Chair | Susan Liautaud[2] | ||||||||||||

| Visitor | Lucy Powell (as Lord President of the Council ex officio) | ||||||||||||

| Chancellor | The Princess Royal (as Chancellor of the University of London) | ||||||||||||

| President and Vice-Chancellor | Larry Kramer | ||||||||||||

Academic staff | 1,910 (2022/23)[3] | ||||||||||||

Administrative staff | 2,520 (2022/23)[3] | ||||||||||||

| Students | 13,295 (2022/23)[4] | ||||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 5,950 (2022/23)[4] | ||||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 7,350 (2022/23)[4] | ||||||||||||

| Location | London , England 51°30′50″N 0°07′00″W / 51.51389°N 0.11667°W | ||||||||||||

| Campus | Urban | ||||||||||||

| Newspaper | The Beaver | ||||||||||||

| Colours | Purple, black and gold[5] | ||||||||||||

| Affiliations | |||||||||||||

| Mascot | Beaver | ||||||||||||

| Website | lse | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a public research university in London, England, and a member institution of the University of London. The school specialises in the social sciences. Founded in 1895 by Fabian Society members Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, Graham Wallas and George Bernard Shaw, LSE joined the University of London in 1900 and established its first degree courses under the auspices of the university in 1901.[6] LSE began awarding its degrees in its own name in 2008,[7] prior to which it awarded degrees of the University of London. It became a university in its own right within the University of London in 2022.[8]

LSE is located in the London Borough of Camden and Westminster, Central London, near the boundary between Covent Garden and Holborn. The area is historically known as Clare Market. LSE has more than 11,000 students, just under seventy per cent of whom come from outside the UK, and 3,300 staff.[9] The university has the fifth-largest endowment of any university in the UK and in 2023/24, it had an income of £525.6 million of which £41.4 million was from research grants.[1] Despite its name, the school is organised into 25 academic departments and institutes which conduct teaching and research across a range of pure and applied social sciences.[9]

LSE is a member of the Russell Group, Association of Commonwealth Universities and the European University Association, and is typically considered part of the "golden triangle" of research universities in the south east of England. The LSE also forms part of CIVICA – The European University of Social Sciences.[10] The 2025 Times and Sunday Times Good University Guide ranked the London School of Economics as the number one university in the United Kingdom and named it their University of the Year.[11] In the 2021 Research Excellence Framework, the school had the third highest grade point average in the United Kingdom (joint with the University of Cambridge).[12]

LSE alumni and faculty include 55 past or present heads of state or government and 20 Nobel laureates. As of 2024, 25 per cent of all 56 Nobel Memorial Prizes in Economics had been awarded, at least in part, to LSE alumni, current staff, or former staff.[13] LSE alumni and faculty have also won 3 Nobel Peace Prizes and 2 Nobel Prizes in Literature.[14][15] The university has educated the most billionaires (11) of any European university according to a 2014 global census of US dollar billionaires.[16]

History

[edit]

Origins

[edit]The London School of Economics and Political Science was founded in 1895[17] by Beatrice and Sidney Webb,[18] initially funded by a bequest of £20,000[19][20] from the estate of Henry Hunt Hutchinson. Hutchinson, a lawyer[19] and member of the Fabian Society,[21][22] left the money in trust, to be put "towards advancing its [The Fabian Society's] objects in any way they [the trustees] deem advisable".[22] The five trustees were Sidney Webb, Edward Pease, Constance Hutchinson, W. S. de Mattos and William Clark.[19]

LSE records that the proposal to establish the school was conceived during a breakfast meeting on 4 August 1894, between the Webbs, Louis Flood, and George Bernard Shaw.[17] The proposal was accepted by the trustees in February 1895[22] and LSE held its first classes in October of that year, in rooms at 9 John Street, Adelphi,[23] in the City of Westminster.

20th century

[edit]The school joined the federal University of London in 1900 and was recognised as a Faculty of Economics of the university. The University of London degrees of BSc (Econ) and DSc (Econ) were established in 1901, the first university degrees dedicated to the social sciences.[23] Expanding rapidly over the following years, the school moved initially to the nearby 10 Adelphi Terrace, then to Clare Market and Houghton Street. The foundation stone of the Old Building, on Houghton Street, was laid by King George V in 1920;[17] the building was opened in 1922.[23]

The school's arms,[24] including its motto and beaver mascot, were adopted in February 1922,[25] on the recommendation of a committee of twelve, including eight students, which was established to research the matter.[26] The Latin motto, rerum cognoscere causas, is taken from Virgil's Georgics. Its English translation is "to Know the Causes of Things"[25] and it was suggested by Professor Edwin Cannan.[17] The beaver mascot was selected for its associations with "foresight, constructiveness, and industrious behaviour".[26]

The 1930s economic debate between LSE and the University of Cambridge is well known in academic circles. The rivalry between academic opinion at LSE and Cambridge goes back to the school's roots when LSE's Edwin Cannan (1861–1935), Professor of Economics, and Cambridge's Professor of Political Economy, Alfred Marshall (1842–1924), the leading economist of the day, argued about the bedrock matter of economics and whether the subject should be considered as an organic whole. (Marshall disapproved of LSE's separate listing of pure theory and its insistence on economic history.)[27]

The dispute also concerned the question of the economist's role, and whether this should be as a detached expert or a practical adviser.[28] Despite the traditional view that the LSE and Cambridge were fierce rivals through the 1920s and 30s, they worked together in the 1920s on the London and Cambridge Economic Service.[29] However, the 1930s brought a return to disputes as economists at the two universities argued over how best to address the economic problems caused by the Great Depression.[30]

The main figures in this debate were John Maynard Keynes from Cambridge and the LSE's Friedrich Hayek. The LSE economist Lionel Robbins was also heavily involved. Starting off as a disagreement over whether demand management or deflation was the better solution to the economic problems of the time, it eventually embraced much wider concepts of economics and macroeconomics. Keynes put forward the theories now known as Keynesian economics, involving the active participation of the state and public sector, while Hayek and Robbins followed the Austrian School, which emphasised free trade and opposed state involvement.[30]

During World War II, the school decamped from London to the University of Cambridge, occupying buildings belonging to Peterhouse.[31]

Following the decision to establish a modern business school within the University of London in the mid-1960s, the idea was discussed of setting up a "Joint School of Administration, Economics, and Technology" between the LSE and Imperial College. However, this avenue was not pursued and instead, the London Business School was created as a college of the university.[32]

In 1966, the appointment of Sir Walter Adams as director sparked opposition from the student union and student protests. Adams had previously been principal of the University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, and the students objected to his failure to oppose Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence and cooperation with the white minority government. This broadened into wider concerns about links between the LSE and its governors and investments in Rhodesia and South Africa and concerns over LSE's response to student protests. These led to the closure of the school for 25 days in 1969 after a student attempt to dismantle the school gates resulted in the arrest of over 30 students. Injunctions were taken out against 13 students (nine from LSE), with three students ultimately being suspended, two foreign students being deported, and two staff members seen as supporting the protests being fired.[17][33][34]

In the 1970s, four Nobel Memorial Prizes in Economic Sciences were awarded to economists associated with the LSE: John Hicks (lecturer 1926–36) in 1972, Friedrich Hayek (lecturer 1931–50) in 1974, James Meade (lecturer 1947–1957) in 1977 and Arthur Lewis (BSc Econ 1937, and the LSE's first Black academic 1938–44) in 1979.[17][35][36]

21st century

[edit]

In the early 21st century, the LSE had a wide impact on British politics. The Guardian described such influence in 2005 when it stated:

Once again the political clout of the school, which seems to be closely wired into parliament, Whitehall, and the Bank of England, is being felt by ministers. ... The strength of LSE is that it is close to the political process: Mervyn King, was a former LSE professor. The former chairman of the House of Commons education committee, Barry Sheerman, sits on its board of governors, along with Labour peer Lord (Frank) Judd. Also on the board are Tory MPs Virginia Bottomley and Richard Shepherd, as well as Lord Saatchi and Lady Howe.[37]

Commenting in 2001 on the rising status of the LSE, the British magazine The Economist stated that "two decades ago the LSE was still the poor relation of the University of London's other colleges. Now... it regularly follows Oxford and Cambridge in league tables of research output and teaching quality and is at least as well-known abroad as Oxbridge". According to the magazine, the school "owes its success to the single-minded, American-style exploitation of its brand name and political connections by the recent directors, particularly Mr Giddens and his predecessor, John Ashworth" and raises money from foreign students' high fees, which are attracted by academic stars such as Richard Sennett.[38]

In 2006, the school published a report disputing the costs of British government proposals to introduce compulsory ID cards.[39][40][41] LSE academics were also represented on numerous national and international bodies in the early 21st century, including the UK Airports Commission,[42] Independent Police Commission,[43] Migration Advisory Committee,[44] UN Advisory Board on Water and Sanitation,[45] London Finance Commission,[46] HS2 Limited,[47] the UK government's Infrastructure Commission[48] and advising on architecture and urbanism for the London 2012 Olympics[49]

The LSE gained its own degree-awarding powers in 2006 and the first LSE degrees (rather than degrees of the University of London) were awarded in 2008.[17]

Following the passage of the University of London Act 2018, the LSE (along with other member institutions of the University of London) announced in early 2019 that they would seek university status in their own right while remaining part of the federal university.[50] Approval of university title was received from the Office for Students in May 2022 and updated Articles of Association formally constituting the school as a university were approved by LSE council 5 July 2022.[51][52]

Controversies

[edit]In February 2011, LSE had to face the consequences of matriculating one of Muammar Gaddafi's sons while accepting a £1.5m donation to the university from his family.[53] LSE director Howard Davies resigned over allegations about the institution's links to the Libyan regime.[54] The LSE announced in a statement that it had accepted his resignation with "great regret" and that it had set up an external inquiry into the school's relationship with the Libyan regime and Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, to be conducted by the former lord chief justice Harry Woolf.[54]

In 2013, the LSE was featured in a BBC Panorama documentary on North Korea, filmed inside the repressive regime by undercover journalists attached to a trip by the LSE's Grimshaw Club, a student society of the international relations department. The trip had been sanctioned by high-level North Korean officials.[55][56] The trip caused international media attention as a BBC journalist was posing as a part of LSE.[57] There was debate as to whether this put the students' lives in jeopardy in the repressive regime if a reporter had been exposed.[58] The North Korean government made hostile threats towards the students and LSE after the publicity, which forced an apology from the BBC.[56]

In August 2015, it was revealed that the university was paid approximately £40,000 for a "glowing report" for Camila Batmanghelidjh's charity, Kids Company.[59] The study was used by Batmanghelidjh to prove that the charity provided good value for money and was well managed. The university did not disclose that the study was funded by the charity.

In 2023, the LSE formally cut ties with the LGBT charity Stonewall, a decision which was sharply criticized as transphobic by the LSE Student Union but praised by gender-critical activists as being conducive to freedom of speech.[60][61]

Industrial disputes

[edit]In the summer of 2017, dozens of campus cleaners contracted via Noonan Services went on weekly strikes, protesting outside key buildings and causing significant disruption during end-of-year examinations.[62] The dispute organised by the UVW union was originally over unfair dismissals of cleaners, but had escalated into a broad demand for decent employment rights matching those of LSE's in-house employees.[63] Owen Jones did not cross the picket line after arriving for a debate on grammar schools with Peter Hitchens.[64] It was announced in June 2018 that some 200 outsourced workers at the LSE would be offered in-house contracts.[65]

Since 2014/15, levels of academic casualisation have increased at the LSE, with the number of academics on fixed-term contracts increasing from 47% in 2016/2017 to 59% in 2021/2022,[66] according to Higher Education Statistical Agency data (internal LSE data puts the latest figure at 58.5%).[67] During this same period, comparable universities such as University of Edinburgh, University College London and Imperial all increased their rates of permanent staff relative to those on fixed term contracts.[66] Only Oxford had a higher proportion of casual academic work for the 2021/2022 year (66%) although in contrast to LSE, the proportion remained constant rather than rising.[66] As a result, the student-to-permanent staff ratio at LSE has worsened and had, as of July 2023, the worst student-to-permanent staff ratio among comparable universities in the UK, according to HESA data.[66] According to research conducted by the LSE UCU Branch into staff well-being, 82% of fixed term academic staff at the LSE experienced regular or constant anxiety about their professional futures.[67] In the same survey, overwork and mental health issues were reported as endemic among respondents, with 40% of fellows reporting that their teaching hours exceeded LSE's universal teaching limit of 100 hours per academic year for LSE Fellows.[67]

In response to industrial action, which included not marking student work, taken by UCU in the summer of 2023 over pay and casualised working conditions, the LSE management took the decision to not accept partial performance of duties and to impose pay deductions on academic staff participating in the action.[68] The LSE also introduced an 'Exceptional Degree Classification Schemes' policy,[69] allowing undergraduate and taught postgraduate students to be awarded provisional degrees on the basis of fewer grades than normally required. In the event that the final classification (once all marks are available) is lower than the provisional classification, the higher provisional classification will stand as the degree classification.[69]

The World Turned Upside Down

[edit]

A sculpture by Mark Wallinger, The World Turned Upside Down, which features a globe resting on its north pole, was installed in Sheffield Street on the LSE campus on 26 March 2019. The artwork attracted controversy for showing Taiwan as a sovereign state rather than as part of China,[70][71][72] Lhasa being denoted as a full capital and depicting boundaries between India and China as recognised internationally. The sculpture also did not depict the State of Palestine as a separate country from Israel.

After protests and reactions from both Chinese and Taiwanese students,[73][74] The university decided later that year that it would retain the original design which chromatically displayed the PRC and Taiwan as different entities consistent with the status quo, but with the addition of an asterisk beside the name of Taiwan and a corresponding placard that clarified the institution's position regarding the controversy.[75][76]

Campus and estate

[edit]

Since 1902, LSE has been based at Clare Market and Houghton Street (first syllable pronounced "How")[77] in Westminster. It is surrounded by a number of important institutions including the Royal Courts of Justice, all four Inns of Courts, Royal College of Surgeons, Sir John Soane's Museum, and the West End is immediately across Kingsway from campus, which also borders the City of London and is within walking distance to Trafalgar Square and the Houses of Parliament.

In 1920, King George V laid the foundation of the Old Building. The campus now occupies an almost continuous group of around 30 buildings between Kingsway and Aldwych. Alongside teaching and academic space, the institution owns 11 student halls of residence across London, a West End theatre (the Peacock), early years centre, NHS medical centre and extensive sports ground in Berrylands, south London. LSE operates the George IV public house[78] and the students' union operates the Three Tuns bar.[79] The school's campus is noted for its numerous public art installations, which include Richard Wilson's Square the Block,[80] Michael Brown's Blue Rain,[81] Christopher Le Brun's Desert Window,[82] and Turner Prize-winner Mark Wallinger's The World Turned Upside Down.[83][84][85]

Since the early 2000s, the campus has undergone an extensive refurbishment project and a major fund-raising "Campaign for LSE" raised over £100 million in what was one of the largest university fund-raising exercises outside North America. This process began with the £35 million renovation of the British Library of Political and Economic Science by Foster and Partners.[86]

In 2003, LSE purchased the former Public Trustee building at 24 Kingsway and engaged Sir Nicholas Grimshaw to redesign it into an ultra-modern educational facility at a total cost of over £45 million – increasing the size of the campus by 120,000 square feet (11,000 m2). The New Academic Building opened for teaching in October 2008, with an official opening by Her Majesty the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh on 5 November 2008.[87] In November 2009 the school purchased the adjacent Sardinia House to house three academic departments and the nearby Old White Horse public house, before acquiring the freehold of the grade-II listed Land Registry Building at 32 Lincoln's Inn Fields in October 2010, which was reopened in March 2013 by The Princess Royal as the new home for the Department of Economics, International Growth Centre and its associated economic research centres. In 2015, LSE brought its ownership of buildings on Lincoln's Inn Fields to six, with the purchase of 5 Lincoln's Inn Fields on the north side of the square, which has since been converted into faculty accommodation.[88]

Saw Swee Hock Student Centre

[edit]The first new campus building for more than 40 years, the Saw Swee Hock Student Centre, named after the Singaporean statistician and philanthropist, opened in January 2014 following an architectural design competition managed by RIBA Competitions.[89][90] The building provides accommodation for the LSE Students' Union, LSE accommodation office and LSE careers service as well as a bar, events space, gymnasium, rooftop terrace, learning café, dance studio, and media centre.[91] Designed by architectural practice O'Donnell and Tuomey, the building achieved a BREEAM 'Outstanding' rating for environmental sustainability, won multiple awards including the RIBA National Award and London Building of the Year Award, and was shortlisted for the Stirling Prize.[92][93][94][95]

Centre Building

[edit]The Centre Building, situated opposite the British Library of Political and Economic Science, opened in June 2019. Designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour and Partners following a RIBA competition, the 13-storey building includes 14 seminar rooms seating between 20 and 60, 234 study spaces, a 200-seater auditorium, as well as three lecture theatres.[96] The building hosts the School of Public Policy, the Departments of Government and International Relations, the European Institute, and the International Inequalities Institute. It includes publicly accessible roof terraces and a renovated square at the centre of campus.[97][98][99] The building design was recognised with RIBA's London Award and National Award in 2021.[100][101][102][103]

Marshall Building

[edit]The Marshall Building, located at 44 Lincoln's Inn Fields, opened in January 2022.[104] Designed by Grafton Architects and named after British investor Paul Marshall, the building houses the Departments of Management, Accounting, and Finance, sports facilities, and the Marshall Institute for Philanthropy and Social Entrepreneurship.[105][106][107] The site was previously home to the Francis Crick Institute's laboratories, which LSE purchased in 2013.[108][109]

Future expansion

[edit]

On 15 November 2017, LSE announced that it acquired the Nuffield Building at 35 Lincoln's Inn Fields from the Royal College of Surgeons and plans to redevelop the site to host the Firoz Lalji Global Hub, the departments of Mathematics, Statistics and Methodology, the Data Science Institute, and conference and executive education facilities. The new building will be designed by David Chipperfield Architects.[110][111][112][113]

Sustainability

[edit]In 2021, LSE claimed to be the first UK university to be independently verified as carbon-neutral, which it achieved by funding rainforest trees to offset emissions through the Finnish organisation (Oy) Compensate.[114][115] However, LSE omitted some of its emissions in its calculation and thus did not offset all of them. While it measured and offset emissions from heating, electricity, and faculty air travel, the school left out other travel-related emissions, as well as emissions from construction and on-campus food. LSE plans to offset the remaining emissions (scope 1 through 3) by 2050.[116][117][118]

Organisation and administration

[edit]Governance

[edit]

Although LSE is a constituent college of the federal University of London, it is in many ways comparable with free-standing, self-governing, and independently funded universities, and it awards its own degrees.

LSE is incorporated under the Companies Act as a company limited by guarantee and is an exempt charity within the meaning of Schedule Two of the Charities Act 1993.[119] The principal governance bodies of the LSE are: the LSE Council; the Court of Governors; the academic board; and the director and director's management team.[119]

The LSE Council is responsible for strategy and its members are company directors of the school. It has specific responsibilities in relation to areas including the monitoring of institutional performance; finance and financial sustainability; audit arrangements; estate strategy; human resource and employment policy; health and safety; "educational character and mission", and student experience. The council is supported in carrying out its role by a number of committees that report directly to it.[119]

The Court of Governors deals with certain constitutional matters and has pre-decision discussions on key policy issues and the involvement of individual governors in the school's activities. The court has the following formal powers: the appointment of members of the court, its subcommittees, and the council; election of the chair and vice chairs of the court and council and honorary fellows of the school; the amendment of the memorandum and articles of association; and the appointment of external auditors.[119]

The academic board is LSE's principal academic body and considers all major issues of general policy affecting the academic life of the school and its development. It is chaired by the director, with staff and student membership, and is supported by its own structure of committees. The vice chair of the academic board serves as a non-director member of the council and makes a termly report to the council.[119] Since the COVID-19 Pandemic, the Academic Board has moved online and has not yet returned to in-person meetings, changing the dynamic of engagement.

President and Vice-Chancellor

[edit]

The president and vice-chancellor (titled director until 2022) is the head of LSE and its chief executive officer, responsible for executive management and leadership on academic issues. The vice-chancellor reports to and is accountable to the council. The vice-chancellor is also the accountable officer for the purposes of the Office for Students financial memorandum. The LSE's current interim vice-chancellor is Eric Neumayer, who replaced Minouche Shafik on 23 June 2023. In July 2023, the LSE announced that Hewlett Foundation head Larry Kramer would become president and vice-chancellor in April 2024.[120]

The president is supported by four pro-vice chancellors with designated portfolios (education; research; planning and resources; faculty development), the school secretary, the chief operating officer, the chief finance officer, and the chief philanthropy and global engagement officer.[121]

| Years | Name |

|---|---|

| 1895–1903 | William Hewins |

| 1903–1908 | Sir Halford Mackinder |

| 1908–1919 | The Hon. William Pember Reeves |

| 1919–1937 | Lord Beveridge |

| 1937–1957 | Sir Alexander Carr-Saunders |

| 1957–1967 | Sir Sydney Caine |

| 1967–1974 | Sir Walter Adams |

| 1974–1984 | Lord Dahrendorf |

| 1984–1990 | Indraprasad Gordhanbhai Patel |

| 1990–1996 | Sir John Ashworth |

| 1996–2003 | Lord Giddens |

| 2003–2011 | Sir Howard Davies |

| 2011–2012 | Judith Rees (interim) |

| 2012–2016† | Craig Calhoun |

| 2016–2017 | Julia Black (interim) |

| 2017–2023 | Minouche Shafik |

| 2023–2024 | Eric Neumayer (interim) |

| 2024–present | Larry Kramer |

† Titled as director and president[122]

Academic departments and institutes

[edit]LSE's research and teaching are organised into a network of independent academic departments established by the LSE Council, the school's governing body, on the advice of the academic board, the school's senior academic authority. There are currently 27 academic departments or institutes.

- Department of Accounting

- Department of Anthropology

- Department of Economic History

- Department of Economics

- Department of Finance

- Department of Geography and Environment

- Department of Gender Studies

- Department of Health Policy

- Department of Government

- Department of International Development

- Department of International History

- Department of International Relations

- Department of Management

- Department of Mathematics

- Department of Media and Communications

- Department of Methodology

- Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method

- Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science

- Department of Social Policy

- Department of Sociology

- Department of Statistics

- European Institute

- International Inequalities Institute

- Institute of Public Affairs

- Language Centre

- LSE Law School

- Marshall Institute for Philanthropy and Social Entrepreneurship[123]

- School of Public Policy

Finances

[edit]In the financial year ending 31 July 2024, the London School of Economics (LSE) had a total income of £525.6 million (2022/23 – £466.1 million) and total expenditure of £344.4 million (2022/23 – £424.8 million).[1] Key sources of income included £316.4 million from tuition fees and education contracts (2022/23 – £295.0 million), £26.8 million from funding body grants (2022/23 – £29.1 million), £41.4 million from research grants and contracts (2022/23 – £39.6 million), £11.6 million from investment income (2022/23 – £7.8 million) and £49.3 million from donations and endowments (2022/23 – £22.7 million).[1]

At year end, the LSE had endowments of £255.5 million (2022/23 – £229.3 million) and total net assets of £1.009 billion (2022/23 – £793.2 million).[1]

The Times Higher Education Pay Survey 2017 revealed that, among larger, non-specialist institutions, LSE professors and academics were the highest paid in the UK, with average incomes of £103,886 and £65,177 respectively.[124]

Endowment

[edit]The LSE is aiming to increase the size of its endowment fund to more than £1bn, which would make it one of the best resourced institutions in the UK and the world. The effort was initiated in 2016 by Lord Myners, then chairman of the LSE's Council and Court of Governors. The plan includes working with wealthy alumni of LSE to make large contributions, increasing the annual budget surplus, and launching a new, widescale alumni donor campaign. The plan to grow LSE's endowment to more than £1bn has been continued by Lord Myners' successors at the LSE.[125] The LSE stated in 2016 that currently "limited endowment funding constrains our ability to offer 'needs blind' admission to students".[126] In the ten-year period between 2015 and 2024, the endowment more than doubled from £113 million to £255 million, making it the fifth-largest endowment of any university in the UK.[127][1]

Academic year

[edit]LSE continues to adopt a three-term structure and has not moved to semesters. Michaelmas Term runs from October to mid-December, Lent Term from mid-January to late March, and Summer Term from late April to mid-June. Certain departments operate reading weeks in early November and mid-February.[128]

Logo, arms and mascot

[edit]

The school's historic coat of arms is used on official documentation including degree certificates and transcripts and includes the motto – rerum cognoscere causas, a line taken from Virgil's Georgics meaning "to know the causes of things", together with the school's mascot – a beaver. Both these symbols, adopted in February 1922, continue to be held in high regard to this day with the beaver chosen because of its representation as "a hard-working and industrious yet sociable animal", attributes that the founders hoped LSE students to both possess and aspire to.[129] The school's weekly newspaper is still entitled The Beaver, Rosebery residence hall's bar is called the Tipsy Beaver and LSE sports teams are known as the Beavers.[130] The institution has two sets of colours – brand and academic – red being the brand colour used on signage, publications and in buildings across campus and purple, black and gold for academic purposes including presentation ceremonies and graduation dress.

LSE's present 'red block' logo was modified as part of a rebrand in the early 2000s. As a trademarked brand, it is carefully protected but can be produced in various forms to reflect different requirements.[131] In its full form it contains the full name of the institution to the right of the block with a further small empty red square at the end, but it is adapted for each academic department or professional service division to provide a cohesive brand across the institution.

Academic profile

[edit]Admissions

[edit]

|

| Domicile[135] and Ethnicity[136] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| British White | 16% | ||

| British Ethnic Minorities[a] | 19% | ||

| International EU | 15% | ||

| International Non-EU | 50% | ||

| Undergraduate Widening Participation Indicators[137][138] | |||

| Female | 53% | ||

| Private School | 30% | ||

| Low Participation Areas[b] | 7% | ||

In 2024, The London School of Economics received 28,000 applications for roughly 1,850 undergraduate places or 15 applicants per place.[139] All undergraduate applications, including international applications, are made through UCAS.[139] LSE had the 8th highest average entry qualification for undergraduates of any UK university in 2021–22, with new students averaging 195 UCAS points, equivalent to just over AAAA in A-level grades.[134] The university gave offers of admission to roughly 12.2% of its undergraduate applicants in 2023, one of the lowest offer rates across the UK. Bsc Economics is the most competitive undergraduate course at the LSE with over 4000 applications for just over 200 places. LLB in Laws comes second with 2600 applications for just over 170 places.[140][141]

Prospective Postgraduate students applying to the LSE are required to have a first or upper second Class UK honours degree, or its foreign equivalent, for master's degrees, while direct entry to the MPhil/PhD programme requires a UK taught master's with merit, or foreign equivalent. Admission to the diploma requires a UK degree or equivalent plus relevant experience.[142] The intake to applications ratio for postgraduate degree programmes is very competitive; the MSc Financial Mathematics had a ratio of just over 4% in 2016.[143][144]

31.6% of LSE's undergraduates are privately educated, the 9th highest proportion amongst mainstream British universities.[145] In the 2016-17 academic year, the university had a domicile breakdown of 33:18:50 of UK:EU:non-EU students respectively with a female-to-male ratio of 52:47.[146]

Programmes and degrees

[edit]As of 2024,[update] the school offers over 40 undergraduate programmes,[147] over 140 taught master's programmes, and research master's and PhD programmes.[148] Subjects pioneered in Britain by LSE include accountancy and sociology, and the school also employed Britain's first full-time lecturer in economic history.[149] Courses are split across more than thirty research centres and nineteen departments, plus a Language Centre.[150] In partnership with the federal University of London, LSE oversees nine BSc programmes as the lead institution which designs the curriculum.[151] Students who chose to study online experience the same unique academic experience as on-campus, they are considered a part of LSE community and they have a variety of options to interact with their university, such as the LSE general course.[152]

Since programmes are all within the social sciences, they closely resemble each other, and undergraduate students usually take at least one course module in a subject outside of their degree for their first and second years of study, promoting a broader education in the social sciences.[153] At undergraduate level, some departments have as few as 90 students across the three years of study.[citation needed] Since September 2010,[citation needed] it has been compulsory for first year undergraduates to participate in LSE 100: Understanding the Causes of Things alongside normal studies.[154]

From 1902, following its absorption into the University of London, until 2007, all degrees were awarded by the federal university in common with all other colleges of the university. This system was changed in 2007 to enable some colleges to award their own degrees.[citation needed] LSE was granted the power to begin awarding its own degrees from July 2008.[7] All students entering from the 2007–08 academic year onwards received an LSE degree, while students who started before this date were issued University of London degrees.[155][156][157] In conjunction with NYU Stern and HEC Paris, LSE also offers the TRIUM Executive MBA. This was globally ranked third among executive MBAs by the Financial Times in 2016.[158]

Research

[edit]According to the 2021 Research Excellence Framework, the London School of Economics was rated joint third (along with the University of Cambridge) in the UK for the quality (GPA) of its research.[159] In the 2014 Research Excellence Framework, LSE had the joint highest percentage of world-leading research among research submitted of any institution that entered more than one unit of assessment[160] and was ranked third by cumulative grade point average with a score of 3.35, beating both University of Oxford and University of Cambridge.[161] It was ranked 23rd in the country for research power by Research Fortnight based on its REF 2014 results, and 28th in research power by the Times Higher Education.[160][162] This followed the Research Assessment Exercise in 2008 where the school was placed second equal nationally on GPA, first for fraction of world-leading (4*) research and fourth for fraction of world-leading or internationally excellent (3* and 4*) research in LSE's analysis of the results,[163] fourth equal for GPA and 29th for research power in Times Higher Education's analysis,[160] and 27th in research power by Research Fortnight's analysis.[162]

According to analysis of the REF 2014 subject results by Times Higher Education, the school is the UK's leading research university in terms of GPA of research submitted in business and management; area studies; and communication, cultural and media studies, library and information management, and second in law; politics and international studies; economics and econometrics; and social work and social policy.[164]

Research centres

[edit]The school houses a number of centres including the Centre for the Analysis of Social Exclusion, the Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, the Centre for Macroeconomics, the Centre for Economic Performance, LSE Health and Social Care, the Financial Markets Group (founded by former Bank of England governor Sir Mervyn King), the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment (chaired by Lord Stern), LSE Cities, the UK Department for International Development funded International Growth Centre and one of the six the UK government-backed 'What Works Centres' – the What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth. The Greater London Group was an influential research centre within LSE from the late 1950s on, before being subsumed into the LSE London research group.[165] In February 2015, Angelina Jolie and William Hague launched the UK's first academic Centre on Women, Peace and Security, based at the school. The centre aims to contribute to global women's rights issues, including violence against women and women's engagement in politics, through academic research, a post-graduate teaching program, public engagement, and collaboration with international organisations.[166][167] Furthermore, in May 2016 it was announced that Jolie-Pitt and Hague would join Jane Connors and Madeleine Rees as visiting professors in practice from September 2016.[168]

LSE IDEAS

[edit]LSE IDEAS is a foreign policy think tank at the London School of Economics and Political Science. IDEAS was founded as a think tank for Diplomacy and Strategy in February 2008.[169] It was founded by Professor Michael Cox and Professor Arne Westad. In 2015 it was jointly ranked as world's second-best university think tank for the third year running alongside the LSE Public Policy Group, after Harvard University's Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.[170]

Partnerships

[edit]LSE has academic partnerships in teaching and research with six universities – with Columbia University in New York City and University of California, Berkeley, in Asia with Peking University in Beijing and the National University of Singapore, in Africa with the University of Cape Town, and Europe with Sciences Po in Paris.[171]

Together they offer a range of double or joint degree programmes including an MA in International and World History (with Columbia) and an MSc in international affairs with Peking University, with graduates earning degrees from both institutions.[172] The school also offers joint degrees for specific departments with various other universities including Fudan University in Shanghai, USC in Los Angeles and a Global Studies programme which is offered with a consortium of four European universities – Leipzig, Vienna, Roskilde and Wroclaw. It offers the TRIUM Global Executive MBA programme[173] jointly with Stern School of Business of New York University and HEC School of Management, Paris. It is divided into six modules held in five international business locations over a 16-month period. LSE also offers a Dual Master of Public Administration (MPA) with Global Public Policy Network schools such as Sciences Po Paris,[174] the Hertie School of Governance and National University of Singapore, and a dual MPA-Master of Global Affairs (MGA) degree with the University of Toronto's Munk School of Global Affairs.[175]

The school also runs exchange programmes with a number of international business schools through the Global Master's in Management programme and an undergraduate student exchange programme with the University of California, Berkeley in Political Science. LSE is the only UK member school in the CEMS Alliance, and the LSE Global Master's in Management is the only programme in the UK to offer the CEMS Master's in International Management (CEMS MIM) as a double degree option, allowing students to study at one of 34 CEMS partner universities.[176][177] It also participates in Key Action 1 of the European Union-wide Erasmus+ programme, encouraging staff and student mobility for teaching, although not the other Key Actions in the programme.[178]

The school is a member of the Association of Commonwealth Universities, the European University Association,[179] the G5, the Global Alliance in Management Education, the Russell Group and Universities UK,[180] and is sometimes considered part of the 'Golden Triangle' of universities in south-east England, along with the University of Oxford, the University of Cambridge, University College London, Imperial College London, and King's College London.[181][182][183][184]

LSE's European Institute offers a Double Degree in European and International Public Policy and Politics with Bocconi University in Milan.[185]

Libraries and archives

[edit]

LSE's main library, the British Library of Political and Economic Science, is located in the Lionel Robbins Building, which reopened in 2001 following a two-year renovation by Foster and Partners. Founded in 1896, it is the world's largest library dedicated to social sciences and the United Kingdom's national social sciences library.[186][187] Its collections are recognised for their national and international significance and hold 'Designation' status by the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council (MLA).[188] The library welcomes 1.8 million visits per year by students, staff, and the public and contains over 4 million print volumes, 60,000 online journals, and 29,000 electronic books.[189] The Digital Library contains digitised material from LSE Library collections and also born-digital material that has been collected and preserved in digital formats.[190]

The Women's Library, Britain's main library and archive on women and the women's movement, is located in a purpose-built facility with a reading room and exhibition space in the Lionel Robbins Building. The library relocated from London Metropolitan University in 2014.[191][192][193][194]

The Shaw Library, housed in the Founders' Room in the Old Building, contains the school's collection of fiction and general readings. It functions as a general-purpose reading and common room and hosts lunchtime music concerts, press launches, and the Fabian Window, which was unveiled by Prime Minister Tony Blair in 2006.[195][196]

Several subject-specific libraries exist at LSE, including the Seligman Library for Anthropology, the Himmelweit Library for Social Psychology, the Leverhulme Library for Statistics, the Robert McKenzie Library for Sociology, the Michael Wise Library for Geography, and the Gender Institute Library. Additionally, LSE staff and some students are permitted to access and borrow items from Senate House Library, the SOAS Library, and select institutions through the SCONUL Access scheme.[197][198][199]

LSE Summer School

[edit]The original LSE Summer School was established in 1989 and has since expanded to offer over 70 three-week courses in accounting, finance, economics, English language, international relations, government, law and management each July and August.[200] It is advertised as the largest and one of the most well-established university Summer Schools of its kind in Europe.[201]

In recent years, the school has expanded its summer schools both abroad and into executive education with the LSE-PKU Summer School in Beijing (run with Peking University), the LSE-UCT July School in Cape Town (run with the University of Cape Town) and the Executive Summer School at its London campus. In 2011, it also launched a Methods Summer Programme. Together these courses welcome over 5,000 participants from over 130 countries and some of the top colleges and universities around the world, as well as professionals from several multinational institutions. Participants are housed in LSE halls of residence or their overseas equivalents, and the Summer School provides a full social programme including guest lectures and receptions.[202]

Public lectures

[edit]

Public lectures hosted by the LSE Events office, are open to students, alumni and the general public. As well as leading academics and commentators, speakers frequently include prominent national and international figures such as ambassadors, CEOs, Members of Parliament, and heads of state. A number of these are broadcast live around the world via the school's website.[203] LSE organises over 200 public events every year.[204]

Prominent speakers have included Kofi Annan, Ben Bernanke, Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, David Cameron, Noam Chomsky, Bill Clinton, Philip Craven, Niall Ferguson, Vicente Fox, Milton Friedman, Muammar Gaddafi, Julia Gillard, Alan Greenspan, Tenzin Gyatso, Lee Hsien Loong, Boris Johnson, David Harvey, Jean Tirole, Angelina Jolie, Paul Krugman, Dmitri Medvedev, Mario Monti, George Osborne, Robert Peston, Sebastián Piñera, Kevin Rudd, Jeffrey Sachs, Gerhard Schroeder, Carlos D. Mesa, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Aung San Suu Kyi, Amartya Sen, George Soros and Rowan Williams. Previously, the school has hosted figures including Nelson Mandela and Margaret Thatcher.[205]

There are also a number of annual lecture series hosted by various departments. These include but are not limited to the Malinowski Memorial Lectures hosted by the department of anthropology, the Lionel Robbins Memorial Lectures and the Ralph Miliband programme.[206]

Publishing

[edit]In 2018, the university launched LSE Press in partnership with Ubiquity Press. This is intended to publish open-access journals and books in the social sciences. The first journal to be published by the press was the Journal of Illicit Economies and Development, edited by John Collins, executive director of LSE's International Drug Policy Unit. The press is managed through the LSE Library.[207]

Rankings and reputation

[edit]| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2025)[208] | 3 |

| Guardian (2025)[209] | 4 |

| Times / Sunday Times (2025)[210] | 1 |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2024)[211] | 151–200 |

| QS (2025)[212] | 50= |

| THE (2025)[213] | 50= |

LSE is ranked first in the UK in the Times/Sunday Times Good University Guide 2025, in addition to being awarded University of the Year. It was also named as runner-up for University of the Year for Graduate Employment.[214]

LSE is ranked third in the UK in the Complete University Guide 2025,[215] and fourth in the Guardian University Guide 2025.[209]

In 2024, the QS World University Rankings placed the LSE among the global top five universities in the subjects of Communication and Media Studies (2nd), Geography (2nd), Philosophy (2nd), Social Policy and Administration (3rd), Development Studies (3rd), History (4th), Sociology (4th) and Politics (5th). It further ranked among the global top ten in Finance, Management, Economics, and Law. Overall, it was ranked 56th internationally.

Ian Diamond, former chief executive of the Economic and Social Research Council and later vice-chancellor of the University of Aberdeen, a member of the THE editorial board, wrote to Times Higher Education in 2007, saying: "The use of a citation database must have an impact because such databases do not have as wide a cover of the social sciences (or arts and humanities) as the natural sciences. Hence the low position of the London School of Economics, caused primarily by its citations score, is a result not of the output of an outstanding institution but the database and the fact that the LSE does not have the counterweight of a large natural science base."[216]

The 2024 Times Higher Education World University Rankings place LSE 8th for social sciences in the world, 11th for business and economics, 14th for law and 35th for arts and humanities, ranking the university 46th globally.[217] The Academic Ranking of World Universities ("Shanghai Ranking") for 2023 ranked LSE 7th in Political Science, 8th in Economics and 8th in Finance, placing it in the 151–200 range.[218]

According to data released by the Department for Education in 2018, LSE was rated as the best university for boosting graduate earnings, with male graduates seeing a 47.2% increase in earnings and female graduates seeing a 38.2% increase in earnings compared to the average graduate.[219]

According to Wealth-X and UBS's "Billionaire Census" in 2014, LSE ranked 10th in the list of 20 schools that have produced the most billionaire alumni.[220] The LSE was the only UK university to make the list.

In the 2020 National Student Survey LSE came 64th out of 154 for overall student satisfaction.[221] The LSE had scored well below its benchmark on this measure in previous years, coming 145th out of 148 in 2017.[222][223] The increase in student satisfaction in 2020 led to a climb of 14 places to fifth in the 2021 Guardian ranking.[224]

Student life

[edit]

Student body

[edit]In the 2015–16 academic year there were 10,833 full-time students and around 700 part-time students at the university. Of these, approximately 7,500 came from outside the United Kingdom (approximately 70% of the total student body), making LSE a highly international school with over 160 countries represented.[225] LSE had more countries represented by students than the UN.[226] 32% of LSE's students come from Asia, 10% from North America, 2% each from South America and Africa. Combined over 100 languages are spoken at LSE.[227] Over half of LSE's students are postgraduates,[228] and there is approximately an equal split between genders with 51% male and 49% female students.[228] Alumni total over 160,000, covering over 190 countries with more than 80 active alumni groups.[9]

Students' Union

[edit]

The LSE Students' Union (LSESU) is affiliated to the National Union of Students and is responsible for campaigning and lobbying the school on behalf of students as well providing student support and the organisation and undertaking of entertainment events and student societies. It is often regarded as the most politically active in Britain – a reputation it has held since the well documented LSE student riots in 1966–67 and 1968–69,[229][230] which made international headlines. In 2015, the school was awarded the top spot for student nightlife by The Guardian newspaper[231] due in part to its central location and provision of over 200 societies, 40 sports clubs, a Raising and Giving (RAG) branch and a thriving media group. In 2013, the union moved into a purpose-built new building – the Saw Swee Hock Student Centre on the Aldwych campus.[232]

A weekly student newspaper The Beaver, is published each Tuesday during term time and is amongst the oldest student newspapers in the country. It sits alongside a radio station, Pulse! which has existed since 1999 and a television station LooSE Television since 2005. The Clare Market Review one of Britain's oldest student publications was revived in 2008.[233] Over £150,000 is raised for charity each year through the RAG (Raising and Giving), the fundraising arm of the Students' Union,[234] which was started in 1980 by then Student Union Entertainments Officer and former New Zealand MP Tim Barnett.[235]

Sporting activity is coordinated by the LSE Athletics Union, which is a constituent of British Universities & Colleges Sport (BUCS).[233]

Student housing

[edit]

LSE owns or operates 10 halls of residence in and around central London and there are also two halls owned by urbanest and five intercollegiate halls (shared with other constituent colleges of the University of London) within a 3-mile radius of the school, for a total of over 4,000 places.[236] Most residences take both undergraduates and postgraduates, although Carr-Saunders Hall and Passfield Hall are undergraduate only, and Butler's Wharf Residence, Grosvenor House and Lillian Knowles House are reserved for postgraduates. Sidney Webb House, managed by Unite Students, takes postgraduates and continuing students.[237] There are also flats available on Anson and Carleton roads, which are reserved for students with children.[238]

The school guarantees accommodation for all first-year undergraduate students and many of the school's larger postgraduate population are also catered for, with some specific residences available for postgraduate living.[239] Whilst none of the residences are located at the Aldwych campus, the closest, Grosvenor House is within a five-minute walk from the school in Covent Garden, whilst the farthest residences (Nutford and Butler's Wharf) are approximately forty-five minutes by Tube or Bus.

Each residence accommodates a mixture of students both home and international, male and female, and, usually, undergraduate and postgraduate. New undergraduate students (including General Course students) occupy approximately 55% of all spaces, with postgraduates taking approximately 40% and continuing students about 5% of places.[239]

The largest LSE student residence, Bankside House, a refurbished early 1950s office block and former headquarters of the Central Electricity Generating Board,[240] opened to students in 1996 and is fully catered, accommodating 617 students across eight floors overlooking the River Thames. It is located behind the Tate Modern art gallery on the south bank of the river.[241][242] The second-largest residence, the High Holborn Residence in High Holborn, was opened in 1995 and is approximately 10 minutes walk from the main campus. It is self-catering, accommodating 447 students in flats of four our five bedrooms with shared facilities.[243]

Notable people

[edit]-

Jomo Kenyatta, President of Kenya (1964–1978)

-

K. R. Narayanan, President of India (1997–2002)

-

Romano Prodi, Prime Minister of Italy (1996–1998; 2006–2008) and President of the European Commission (1999–2004)

-

Pierre Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada (1968–1979; 1980–1984)

-

Tharman Shanmugaratnam, the 9th President of Singapore.

-

Mwai Kibaki, 3rd President of Kenya (2002–2013)

-

Kim Campbell, Prime Minister of Canada (1993)

-

B. R. Ambedkar, The chief architect of the Indian Constitution

-

Heinrich Brüning, Chancellor of Germany (1930–1932)

-

George Soros, billionaire investor, philanthropist and political activist

-

Tony Fernandes, Chief executive officer of the low-cost carrier, AirAsia

-

Kamisese Mara, founding father and Prime Minister of Fiji (1970–1987; 1987–1992)

-

Jason Furman, 28th Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers

-

Preeti Sudan Chairperson of the Union Public Service Commission.

-

David Rockefeller Former Chairman and CEO of Chase Bank

The LSE has a long list of notable alumni and staff, spanning the fields of all scholarship provided by the school.[244] The school has over 50 fellows of the British Academy on its staff, while other notable former staff members include Brian Barry, Christopher Greenwood, Maurice Cranston, Anthony Giddens, Harold Laski, Ralph Miliband, Michael Oakeshott, A. W. Philips, Karl Popper, Lionel Robbins, Susan Strange, Bob Ward and Charles Webster. Mervyn King, the former Governor of the Bank of England, is also a former professor of economics.

Of the current 9 members of the Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee the following five have affiliation to the LSE: Jonathan Haskel (alumnus), Michael Saunders (alumnus), Gertjan Vlieghe (alumnus), Silvana Tenereyro (current professor of economics) and Governor Andrew Bailey (former Research Officer).

In the political arena notable alumni and staff include 53 past or present heads of state, 20 members of the current British House of Commons and 46 members of the current House of Lords. Former British Prime Minister Clement Attlee taught at the school from 1912 to 1923. In recent British politics, former LSE students include Virginia Bottomley, Yvette Cooper, Edwina Currie, Frank Dobson, Margaret Hodge, Robert Kilroy-Silk, former UK Labour Party leader Ed Miliband and former UK Liberal Democrats leader Jo Swinson. Internationally, the current and first female president of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen, Brazilian defence minister Celso Amorim, Costa Rican President Óscar Arias, former Japanese Prime Minister Taro Aso, Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, President of India K. R. Narayanan, President of the Republic of China (Taiwan) Tsai Ing-wen, Italian prime minister and president of the European Commission, Romano Prodi, French Foreign Minister and president of the Constitutional Council Roland Dumas[245] as well as Singapore's President Tharman Shanmugaratnam all studied at LSE. A notable number of LSE students have also played a role in the Barack Obama administration, including Pete Rouse, Peter R. Orszag, Mona Sutphen, Paul Volcker and Jason Furman.[246] Physician Vanessa Kerry and American journalist Susan Rasky are also alumnae of the LSE. Notable American Monica Lewinsky pursued her MSc in Social Psychology at the LSE.Current leader of the opposition of the Sri Lankan government Sajith Premadasa also studied there.

Business people who studied at LSE include the CEO of AirAsia Tony Fernandes, former CEO of General Motors Daniel Akerson, director of Louis Vuitton Delphine Arnault, founder of easyJet Stelios Haji-Ioannou, CEO of Abercrombie & Fitch Michael S. Jeffries, Greek business magnate Spiros Latsis, American banker David Rockefeller, CEO of Newsmax Media Christopher Ruddy, founder of advertising agency Saatchi and Saatchi Maurice Saatchi, hedge fund managers George Soros and Michael Platt and Andreas Utermann, former CEO of Allianz Global Investors.

The LSE has also produced many notable lawyers and judges, including Manfred Lachs (former President of the International Court of Justice), Dorab Patel (former Justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan), Mónica Feria Tinta (British-Peruvian barrister specialising in international law), Anthony Kennedy (former Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States), chief architect of the Indian Constitution and jurist B. R. Ambedkar.

A survey by employment specialists Emolument.com found that it on average took LSE graduates 11.6 years in the workforce to begin earning base salaries in excess of £500,000; the shortest timespan of any university in the United Kingdom.[247]

Convicted British terrorist, Omar Saeed Sheikh, studied statistics at LSE, but did not graduate. He served five years in an Indian prison for kidnapping British tourists in 1994. In 2002, he was arrested and convicted in the kidnapping and murder of Daniel Pearl. The Guardian reported that Sheikh came into contact with radical Islamists at the LSE.[248]

Faculty and Nobel laureates

[edit]As of 2024, 20 Nobel Prizes in economics, peace and literature are officially recognised as having been awarded to LSE alumni and staff.[244]

-

Clement Attlee, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1945–1951). [Nominated for 1955 Peace Prize - none awarded]

-

Ronald Coase – awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1991

-

Christopher A. Pissarides – awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2010 – currently Regius Professor of Economics at LSE

-

Amartya Sen, Indian economist, former professor and Nobel laureate

LSE in literature and other media

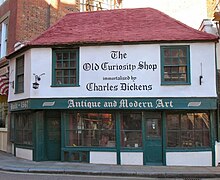

[edit]The London School of Economics has been mentioned and formed the basis of setting for numerous works of fiction and in popular culture. The first notable mention of the LSE was in literature was in the epilogue to Bernard Shaw's 1912 play Pygmalion, Eliza Doolittle is sent to the LSE.[249]

In around a dozen other novels, the LSE was mentioned as short-hand for a character being witty and clever but outside the establishment. This is best exhibited by Ian Fleming's CV of James Bond that included the detail that his father, Andrew, is an LSE graduate.[250] These occurrences have continued into contemporary fiction: Lenny is the young 'hip' LSE graduate and criminologist in Jake Arnott's tour of the London underworld in The Long Firm. Robert Harris' Enigma includes Baxter, a code breaker with leftist views, who has been an LSE lecturer before the war and My Revolutions by Hari Kunzru traces the career of Chris Carver aka Michael Frame who travels from LSE student radical to terrorist and on to middle England.[250]

LSE alumna Hilary Mantel, in The Experience of Love, never mentions LSE by name but Houghton Street, the corridors of the LSE Old Building and Wright's Bar are immediately recognisable references to the campus of the school. A. S. Byatt's The Children's Book returns to LSE's Fabian roots with a plot inspired in part by the life of children's writer E. Nesbitt and Fabian Hubert Bland, and characters that choose LSE over older educational establishments (namely Oxford and Cambridge).

On the small screen, the popular 1980s British sitcom Yes Minister and Yes Prime Minister make regular references to the LSE with Minister Jim Hacker (later Prime Minister) and Sir Mark Spencer (special advisor to the Prime Minister) regularly being subtly ridiculed for having attended the LSE.[251] A fictional LSE graduate also appears in season three episode six of the US series, Mad Men.[251] The popular American series The West Wing following the Democratic administration of Josiah (Jed) Bartlet makes several references to Josiah Bartlet being an alumnus of the LSE.[251] Other fictional LSE alumni are present in Spooks, at least one episode of The Professionals and The Blacklist series.

In movies and motion pictures, in the 2014 action spy thriller Shadow Recruit, the young Jack Ryan, based on a Tom Clancy character, proves his academic credentials by walking out of the Old Building as he graduates from the LSE before injuring his spine being shot down in Afghanistan.[251] The LSE is acknowledged in The Social Network naming the institution along with Oxford and Cambridge universities in a reference to the rapid growth Facebook enjoyed both within and outside the United States in its early years.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Includes those who indicate that they identify as Asian, Black, Mixed Heritage, Arab or any other ethnicity except White.

- ^ Calculated from the Polar4 measure, using Quintile1, in England and Wales. Calculated from the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) measure, using SIMD20, in Scotland.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "Financial Statements for the Year to 31 July 2024" (PDF). London School of Economics. p. 56. Retrieved 12 December 2024.

- ^ "Council". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 2 August 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Who's working in HE?". www.hesa.ac.uk. Higher Education Statistics Agency.

- ^ a b c "Where do HE students study? | HESA". hesa.ac.uk. Higher Education Statistics Agency.

- ^ "Woolen Scarf with Crest Embroidery". LSE Students' Union. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ "Beginnings : LSE : The Founders" (PDF). London School of Economics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Academic dress". The London School of Economics and Political Science. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

Since the granting of its own degree awarding powers in July 2008, students have worn LSE-specific gowns

- ^ Susan Liautaud. "Chair's Blog: Summer Term 2022". Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ a b c "About LSE – Key facts". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "LSE becomes the eighth full member of CIVICA – The European University of Social Sciences" (Press release). CIVICA. 7 July 2020. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ "UK university rankings 2025". The Times. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ Simon Baker; Jack Grove. "REF 2021: Golden triangle looks set to lose funding share". Times Higher Education. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Science, London School of Economics and Political. "LSE people". London School of Economics and Political Science. Retrieved 19 November 2024.

- ^ "LSE People: Nobel Prize Winners". London School of Economics and Political Science. Archived from the original on 23 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ "All Prizes in Economic Sciences". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ "Where do billionaires go to university?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Our history". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ "Meet our founders". London School of Economics and Political Science. London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "London School of Economics and Political Science". London School of Economics and Political Science. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ C. C. Heyde; Eugene Seneta (2001). Statisticians of the Centuries. Springer. p. 279. ISBN 9780387952833. Archived from the original on 10 July 2023. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ Mark K. Smith (30 August 2000). "The London School of Economics and informal education". Archived from the original on 15 October 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ a b c "London School of Economics and Political Science Archives catalogue". London School of Economics. 2008. Archived from the original on 11 June 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ a b c "LSE 1895". London School of Economics. 2000. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ Plant, Arnold. "File:"Coat of arms of the London School of Economics and Political Science"". Institute of Education. Archived from the original on 31 May 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ a b "London School of Economics". Beginnings: The History of Higher Education in Bloomsbury and Westminster. Institute of Education. Archived from the original on 26 September 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ a b "London School of Economics Online Community – Member Services". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 8 September 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ Dahrendorf (1995), p.210-213

- ^ Gerard Loot, cited in Dahrendorf (1995), P.212

- ^ Robert A. Cord (2016). "The London and Cambridge Economic Service: history and contributions". Cambridge Journal of Economics. 41 (1): 307–326. doi:10.1093/cje/bew020. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Debate with Cambridge". LSE timeline 1895–1995. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ "Peterhouse Images". Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ "History of the department". LSE Department of Management. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ Sue Donnelly (18 February 2019). "Opposing a Director". Lse History. London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ Sue Donnelly (6 March 2019). "Storming the gates and closing the School". Lse History. London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ "James Meade". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ Sue Donnelly (23 January 2015). "Arthur Lewis at LSE – one of our best teachers". Lse History. London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ "A Time Honoured Tradition a". The Guardian. London. 27 June 2005. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "The brain trade". The Economist. 5 July 2001. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ "Politics "Ministers press on with ID cards"". 17 January 2006. Archived from the original on 27 June 2006. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ^ "LSE ID Card Report" (PDF). The Guardian. London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "Government staves off ID rebels". BBC News. 14 February 2006. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ^ "UK Airports Commission". UK Government. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ "Policing for a better Britain". London School of Economics. 25 November 2013. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ "Professor David Metcalf". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Professor Judith Rees". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "LSE Professor calls for London to have a greater say over its taxes". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Topham, Gwyn (5 November 2013). "HS2 report overstated benefits by six to eight times, experts say". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 July 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ "LSE recommendations behind UK government's new Infrastructure Commission". Centre for Economic Performance. 5 October 2015. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Professor Ricky Burdett – Commissioner A". Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ "UCL statement on University of London Act 2018". University College London. 11 March 2019. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Susan Liautaud. "Chair's Blog: Summer Term 2022". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Articles of Association" (PDF). London School of Economics. 5 July 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Owen, Jonathan (27 February 2011). "LSE embroiled in row over authorship of Gaddafi's son's PhD thesis and a £1.5m gift to university's coffers". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ a b Vasagar, Jeevan; Syal, Rajeev (4 March 2011). "LSE head quits over Gaddafi scandal". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "BBC Panorama news documentary sent undercover reporter to North Korea with students". News.com.au. 15 April 2013. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ a b Tara Conlan. "BBC to apologise to LSE over John Sweeney's North Korea documentary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ Josh Halliday. "Students say LSE has placed them at 'more risk' from North Korea". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ Sinha, Kounteya (18 April 2013). "North Korea sends threats to LSE students". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ "London School of Economics was paid £40,000 for glowing report on Kids Company". Times Higher Education. 12 August 2015. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Somerville, Ewan. "University that launched Britain's first Pride march cuts ties with Stonewall". Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Armstrong, John. "LSE is right to cut ties with Stonewall". Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Justice for the LSE Cleaners!". Engenderings. 14 November 2016. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ Jones, Owen (25 May 2017). "The courage of the LSE's striking cleaners can give us all hope | Owen Jones". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 25 February 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "Left-wing columnist Owen Jones snubs LSE debate in solidarity with striking cleaners". International Business Times UK. 18 May 2017. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "Rebellion at the LSE: a cleaning sector inquiry". Notes From Below. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d HESA (2023). "HE academic staff by HE provider and employment conditions, Academic years 2014/15 to 2021/22". HESA. Archived from the original on 27 July 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ a b c ""The Crisis of Academic Casualisation at LSE"". LSE UCU Report 2023. 2023. Archived from the original on 27 July 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ LSE (2023). ""Industrial Action: marking and assessment boycott – frequently asked questions (FAQs) for staff and managers"" (PDF). London School of Economics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 July 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ a b LSE Registrar's Division, Student Services (June 2023). ""Marking and Assessment Boycott Summer 2023 Exceptional Degree Classification Schemes for Provisional Classifications" (PDF)" (PDF). London School of Economics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 July 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ Martin Bailey (April 5, 2019), "Wallinger's upside-down globe outside LSE angers Chinese students for portraying Taiwan as an independent state", The Art Newspaper. Archived 2 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Chung, Lawrence (4 April 2019). "Taipei complains about London university's decision to alter artwork and portray Taiwan as part of China". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ O'Connor, Tom (26 March 2019). "China destroys 30,000 world maps showing 'problematic' borders of Taiwan and India". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ Wu, Joseph (5 April 2019). "Taiwan Foreign Minister writes open letter protesting LSE's decision to change depiction of Taiwan on sculpture". Taipei Representative Office in the U.K. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ Parker, Charlie. "London School of Economics in a world of trouble over globe artwork". The Times. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ Lin Chia-nan (11 July 2019). "Ministry lauds LSE for globe color decision". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ "Taiwan still distinct from China but given asterisk on LSE art work". Focus Taiwan. 10 July 2019. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ the LSE

- ^ "Restaurants and cafes on campus". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 24 June 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ "Food and drink". London School of Economics and Political Science. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "LSE unveils new Richard Wilson sculpture, Square the Block". London School of Economics and Political Science. London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "Blue Rain at LSE". London School of Economics and Political Science. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "Stained Glass Window: Christopher Le Brun's Sacred Desert Window". London School of Economics and Political Science. London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Science, London School of Economics and Political (26 March 2019). ""The World Turned Upside Down" – LSE unveils new sculpture by Mark Wallinger". London School of Economics and Political Science. Archived from the original on 10 July 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2022.