Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

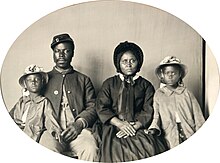

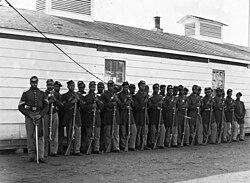

African Americans, including former enslaved individuals, served in the American Civil War. The 186,097 black men who joined the Union Army included 7,122 officers and 178,975 enlisted soldiers.[1] Approximately 20,000 black sailors served in the Union Navy and formed a large percentage of many ships' crews.[2] Later in the war, many regiments were recruited and organized as the United States Colored Troops, which reinforced the Northern forces substantially during the conflict's last two years. Both Northern Free Negro and Southern runaway slaves joined the fight. Throughout the course of the war, black soldiers served in forty major battles and hundreds of more minor skirmishes; sixteen African Americans received the Medal of Honor.[2]

For the Confederacy, both free and enslaved black Americans were used for manual labor, but the issue of whether to arm them, and under what terms, became a major source of debate within the Confederate Congress, the President's Cabinet, and C.S. War Department staff. In general, newspapers, politicians, and army leaders alike were hostile to any efforts to arm blacks. The war's desperate circumstances meant that the Confederacy changed their policy in the last month of the war; in March 1865, a small program attempted to recruit, train, and arm blacks, but no significant numbers were ever raised or recruited, and those that were never saw combat.[3]

Union

[edit]Our Presidents, Governors, Generals and Secretaries are calling, with almost frantic vehemence, for men.-"Men! men! send us men!" they scream, or the cause of the Union is gone...and yet these very officers, representing the people and the Government, steadily, and persistently refuse to receive the very class of men which have a deeper interest in the defeat and humiliation of the rebels than all others.

Proposals to raise African American regiments in the Union's war efforts were at first met with trepidation by officials within the Union command structure, President Abraham Lincoln included. Concerns over the response of the border states (of which one, Maryland, surrounded in part the capital of Washington D.C.), the response of white soldiers and officers, as well as the effectiveness of a fighting force composed of black men were raised.[5]: 165–167 [6] Despite official reluctance from above, the number of white volunteers dropped throughout the war, and black soldiers were needed, whether the population liked it or not.[7] However, African Americans had been volunteering since the first days of war on both sides, though many were turned down.[8]

On July 17, 1862, the U.S. Congress passed two statutes allowing for the enlistment of "colored" troops (African Americans)[9] but official enrollment occurred only after the effective date of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. However, state and local militia units had already begun enlisting black men, including the "Black Brigade of Cincinnati", raised in September 1862 to help provide manpower to thwart a feared Confederate raid on Cincinnati from Kentucky, as well as black infantry units raised in Kansas, Missouri, Louisiana, and South Carolina.[10] In March 1863, upon hearing that Andrew Johnson was open to recruiting blacks in Tennessee, Abraham Lincoln wrote him encouragement: "The colored population is the great available, and yet unavailed of, force for restoring the Union. The bare sight of 50,000 armed and drilled black soldiers upon the banks of the Mississippi would end the rebellion at once."[11]

In May 1863, Congress established the Bureau of Colored Troops in an effort to organize black people's efforts in the war.[12]

African Americans served as medical officers after 1863, beginning with Baltimore surgeon Alexander Augusta. Augusta was a senior surgeon, with white assistant surgeons under his command at Fort Stanton, MD.[13]

In actual numbers, African-American soldiers eventually constituted 10% of the entire Union Army (United States Army). Losses among African Americans were high: In the last year and a half and from all reported casualties, approximately 20% of all African Americans enrolled in the military lost their lives during the Civil War.[1]: 16 Notably, their mortality rate was significantly higher than that of white soldiers:

[We] find, according to the revised official data, that of the slightly over two millions troops in the United States Volunteers, over 316,000 died (from all causes), or 15.2%. Of the 67,000 Regular Army (white) troops, 8.6%, or not quite 6,000, died. Of the approximately 180,000 United States Colored Troops, however, over 36,000 died, or 20.5%. In other words, the mortality "rate" amongst the United States Colored Troops in the Civil War was 35% greater than that among other troops, notwithstanding the fact that the former were not enrolled until some eighteen months after the fighting began.

Non-combatant labor duty

[edit]

Escaped slaves who sought refuge in Union Army camps were called contrabands. A number of officers in the field experimented, with varying degrees of success, in using contrabands for manual work in Union Army camps. Eventually they composed black regiments of soldiers. These officers included General David Hunter, General James H. Lane, and General Benjamin F. Butler of Massachusetts.[5]: 165–167 In early 1861, General Butler was the first known Union commander to use black contrabands, in a non-combatant role, to do the physical labor duties, after he refused to return escaped slaves, at Fort Monroe, Virginia, who came to him for asylum from their masters, who sought to capture and reenslave them. In September 1862, free African-American men were conscripted and impressed into forced labor for constructing defensive fortifications, by the police force of the city of Cincinnati, Ohio; however, they were soon released from their forced labor and a call for African-American volunteers was sent out. Some 700 of them volunteered, and they came to be known as the Black Brigade of Cincinnati. Because of the harsh working conditions and the extreme brutality of their Cincinnati police guards, the Union Army, under General Lew Wallace, stepped in to restore order and ensure that the black conscripts received the fair treatment due to soldiers, including the equal pay of privates.

Contrabands were later settled in a number of colonies, such as at the Grand Contraband Camp, Virginia, and in the Port Royal Experiment.

Blacks also participated in activities further behind the lines that helped keep an army functioning, such as at hospitals and the like. Jane E. Schultz wrote of the medical corps that

Approximately 10 percent of the Union's female relief workforce was of African descent: free blacks of diverse education and class background who earned wages or worked without pay in the larger cause of freedom, and runaway slaves who sought sanctuary in military camps and hospitals.[14]

Early battles in 1862 and 1863

[edit]In general, white soldiers and officers believed that black men lacked the ability to fight and fight well. [citation needed] In October 1862, African-American soldiers of the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry, in one of the first engagements involving black troops, silenced their critics by repulsing attacking Confederate guerrillas at the Skirmish at Island Mound, Missouri, in the Western Theatre. By August, 1863, fourteen more Negro State Regiments were in the field and ready for service. Union General Benjamin Butler wrote

Better soldiers never shouldered a musket. I observed a very remarkable trait about them. They learned to handle arms and to march more easily than intelligent white men. My drillmaster could teach a regiment of Negroes that much of the art of war sooner than he could have taught the same number of students from Harvard or Yale.[15]

At the Battle of Port Hudson, Louisiana, May 27, 1863, the African-American soldiers bravely advanced over open ground in the face of deadly artillery fire. Although the attack failed, the black soldiers proved their capability to withstand the heat of battle, with General Nathaniel P. Banks recording in his official report: "Whatever doubt may have existed heretofore as to the efficiency of organizations of this character, the history of this day's proves...in this class of troops effective supporters and defenders."[16] Noted for his bravery was Union Captain Andre Cailloux, who fell early in the battle.[17] This was the first battle involving a formal Federal African-American unit.[18] On June 7, 1863, a garrison consisting mostly of black troops assigned to guard a supply depot during the Vicksburg Campaign found themselves under attack by a larger Confederate force. Recently recruited, minimally trained, and poorly armed, the black soldiers still managed to successfully repulse the attack in the ensuing Battle of Milliken's Bend with the help of federal gunboats from the Tennessee river, despite suffering nearly three times as many casualties as the rebels.[19] At one point in the battle, Confederate General Henry McCulloch noted

The line was formed under a heavy fire from the enemy, and the troops charged the breastworks, carrying it instantly, killing and wounding many of the enemy by their deadly fire, as well as the bayonet. This charge was resisted by the negro portion of the enemy's force with considerable obstinacy, while the white or true Yankee portion ran like whipped curs almost as soon as the charge was ordered.[20]

Fort Wagner, Fort Pillow, and beyond

[edit][The Fifty-fourth Massachusetts] made Fort Wagner such a name to the colored race as Bunker Hill has been for ninety years to the white Yankees.

The most widely-known battle fought by African Americans was the assault on Fort Wagner, off the Charleston coast, South Carolina, by the 54th Massachusetts Infantry on July 18, 1863. The 54th volunteered to lead the assault on the strongly fortified Confederate positions of the earthen/sand embankments (very resistant to artillery fire) on the coastal beach. The soldiers of the 54th scaled the fort's parapet, and were only driven back after brutal hand-to-hand combat. Despite the defeat, the unit was hailed for its valor, which spurred further African-American recruitment, giving the Union a numerical military advantage from a large segment of the population the Confederacy did not attempt to exploit until too late in the closing days of the War. Unfortunately for any African-American soldiers captured during these battles, imprisonment could be even worse than death. Black prisoners were not treated the same as white prisoners. They received no medical attention, harsh punishments, and would not be used in a prisoner exchange because the Confederate states only saw them as escaped slaves fighting against their masters.[22]

After the battle, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton praised the recent performances of black troops in a letter to Abraham Lincoln, stating "Many persons believed, or pretended to believe, and confidentially asserted, that freed slaves would not make good soldiers; they would lack courage, and could not be subjected to military discipline. Facts have shown how groundless were these apprehensions. The slave has proved his manhood, and his capacity as an infantry soldier, at Milliken's Bend, at the assault upon Port Hudson, and the storming of Fort Wagner."[20]

African-American soldiers participated in every major campaign of the war's last year, 1864–1865, except for Sherman's Atlanta Campaign in Georgia, and the following "March to the Sea" to Savannah, by Christmas 1864. The year 1864 was especially eventful for African-American troops. On April 12, 1864, at the Battle of Fort Pillow, in Tennessee, Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest led his 2,500 men against the Union-held fortification, occupied by 292 black and 285 white soldiers.

After driving in the Union pickets and giving the garrison an opportunity to surrender, Forrest's men swarmed into the Fort with little difficulty and drove the Federals down the river's bluff into a deadly crossfire. Casualties were high and only sixty-two of the U.S. Colored Troops survived the fight. Accounts from both Union and Confederate witnesses suggest a massacre.[23] Many believed that the massacre was ordered by Forrest. The battle cry for some black soldiers became "Remember Fort Pillow!"

Six weeks later, Black troops won a notable victory in their first battle of the Overland Campaign in Virginia at the Battle of Wilson's Wharf, successfully defending Fort Pocahontas. Before the battle, Confederate General Fitzhugh Lee sent a surrender demand to the garrison in the fort, warning them if they did not surrender, he would not be "answerable for the consequences." Interpreting this to be a reference to the massacre at Fort Pillow, Union commanding officer Edward A. Wild defiantly refused, responding with a message stating "Present my compliments to General Fitz Lee and tell him to go to hell.” In the ensuing battle, the garrison force repulsed the assault, inflicting 200 casualties with a loss of just 6 killed and 40 wounded.

The Battle of Chaffin's Farm, Virginia, became one of the most heroic engagements involving black troops. On September 29, 1864, the African-American division of the Eighteenth Corps, after being pinned down by Confederate artillery fire for about 30 minutes, charged the earthworks and rushed up the slopes of the heights. During the hour-long engagement the division suffered tremendous casualties. Of the twenty-five African Americans who were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor during the Civil War, fourteen received the honor as a result of their actions at Chaffin's Farm.

Discrimination in pay and assignments

[edit]

Although black soldiers proved themselves as reputable soldiers, discrimination in pay and other areas remained widespread. According to the Militia Act of 1862, soldiers of African descent were to receive $10.00 per month, with an optional deduction for clothing at $3.00. In contrast, white privates received $12.00 per month plus a clothing allowance of $3.50.[25] Many regiments struggled for equal pay, some refusing any money and pay until June 15, 1864, when the Federal Congress granted equal pay for all soldiers.[26][27]

Besides discrimination in pay, colored units were often disproportionately assigned laborer work, rather than combat assignments.[5]: 198 General Daniel Ullman, commander of the Corps d'Afrique, remarked "I fear that many high officials outside of Washington have no other intention than that these men shall be used as diggers and drudges."[28]

African-American contributions to Union war intelligence

[edit]Black people, both enslaved and free, were involved in assisting the Union in matters of intelligence, and their contributions were labeled Black Dispatches.[29] One of these spies was Mary Bowser. Harriet Tubman was also a spy, a nurse, and a cook whose efforts were key to Union victories and survival. Tubman is most widely recognized for her contributions to freeing slaves via the Underground Railroad. However, her contributions to the Union Army were equally important. She used her knowledge of the country's terrain to gain important intelligence for the Union Army. She became the first woman to lead U.S. soldiers into combat when, under the order of Colonel James Montgomery, she took a contingent of soldiers in South Carolina behind enemy lines, destroying plantations and freeing 750 slaves in the process.[30]

Black people routinely assisted Union armies advancing through Confederate territory as scouts, guides, and spies. Confederate General Robert Lee said "The chief source of information to the enemy is through our negroes."[31] In a letter to Confederate high command, Confederate general Patrick Cleburne complained "All along the lines slavery is comparatively valueless to us for labor, but of great and increasing worth to the enemy for information. It is an omnipresent spy system, pointing out our valuable men to the enemy, revealing our positions, purposes, and resources, and yet acting so safely and secretly that there is no means to guard against it. Even in the heart of our country, where our hold upon this secret espionage is firmest, it waits but the opening fire of the enemy's battle line to wake it, like a torpid serpent, into venomous activity."[32]

Union Navy (U.S. Navy)

[edit]Unlike the army, the U.S. Navy had never prohibited black men from serving, though regulations in place since 1840 had required them to be limited to not more than 5% of all enlisted sailors. Thus at the start of the war, the Union Navy differed from the Army in that it allowed black men to enlist and was racially integrated.[33] The Union Navy's official position at the beginning of the war was ambivalence toward the use of either Northern free black people or runaway slaves. The constant stream, however, of escaped slaves seeking refuge aboard Union ships forced the Navy to formulate a policy towards them.[34] Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Wells in a terse order, pointed out the following;

It is not the policy of this Government to invite or encourage this kind of desertion and yet, under the circumstances, no other course...could be adopted without violating every principle of humanity. To return them would be impolitic as well as cruel...you will do well to employ them.

— Gideon Wells, Secretary of the Navy July 22, 1861 [35]

In time, the Union Navy would see almost 16% of its ranks supplied by African Americans, performing in a wide range of enlisted roles.[36] In contrast to the Army, the Navy from the outset not only paid equal wages to white and black sailors, but offered considerably more for even entry-level enlisted positions.[37] Food rations and medical care were also improved over the Army, with the Navy benefiting from a regular stream of supplies from Union-held ports.[38]

Becoming a commissioned officer was out of reach for nearly all black sailors. With rare exceptions, the rank of petty officer was the highest available to black sailors, and in practice, only to free blacks (who often were the only ones with naval careers sufficiently long to earn the rank).[39] Robert Smalls, an escaped slave who freed himself, his crew, and their families by commandeering a Confederate transport ship, CSS Planter, in Charleston harbor, on May 13, 1862, and sailing it from Confederate-controlled waters of the harbor to the U.S. blockade that surrounded it, was given the rank of captain of the steamer "Planter" in December 1864.[40]

Confederacy

[edit]

Confederate Army

[edit]Blacks did not serve in the Confederate Army as combat troops, per law.[2][42][43] Blacks were not merely not recruited; service was actively forbidden by the Confederacy for the majority of its existence.[2] Enslaved blacks were sometimes used for camp labor, however. Other times, when a son or sons in a slaveholding family enlisted, he would take along a family slave to work as a personal servant. Such slaves would perform non-combat duties such as carrying and loading supplies, but they were not soldiers. Still, even these civilian usages were comparatively infrequent. In areas where the Union Army approached, a wave of slave escapes would inevitably follow; Southern blacks would inevitably offer themselves as scouts who knew the territory to the Federals. Confederate armies were rationally nervous about having too many blacks marching with them, as their patchy loyalty to the Confederacy meant that the risk of one turning runaway and informing the Federals as to the rebel army's size and position was substantial. Opposition to arming blacks was even stauncher. Many in the South feared slave revolts already, and arming blacks would make the threat of mistreated slaves overthrowing their masters even greater.[2]

The closest the Confederacy came to seriously attempting to equip colored soldiers in the army proper came in the last few weeks of the war. The Confederate Congress narrowly passed a bill allowing slaves to join the army. The bill did not offer or guarantee an end to their servitude as an incentive to enlist, and only allowed slaves to enlist with the consent of their masters. Even this weak bill, supported by Robert E. Lee, passed only narrowly, by a 9–8 vote in the Senate. President Jefferson Davis signed the law on March 13, 1865, but went beyond the terms in the bill by issuing an order on March 23 to offer freedom to slaves so recruited. The emancipation offered, however, was reliant upon a master's consent; "no slave will be accepted as a recruit unless with his own consent and with the approbation of his master by a written instrument conferring, as far as he may, the rights of a freedman."[44] According to historian William C. Davis, President Davis felt that blacks would not fight unless they were guaranteed their freedom after the war.[45] Gaining this consent from slaveholders, however, was an "unlikely prospect".[2]

THE BATTALION from Camps Winder and Jackson, under the command of Dr. Chambliss, including the company of colored troops under Captain Grimes, will parade on the square on Wednesday evening, at 4* o'clock. This is the first company of negro troops raised in Virginia. It was organized about a month since, by Dr. Chambliss, from the employees of the hospitals, and served on the lines during the recent Sheridan raid.

According to calculations of Virginia's state auditor, some 4,700 free black males and more than 25,000 male slaves between eighteen and forty five years of age were fit for service.[46] Two companies were raised from laborers of two local hospitals-Winder and Jackson-as well as a formal recruiting center created by General Ewell and staffed by Majors James Pegram and Thomas P. Turner.[47]: 125 In all, they managed to recruit about 200 men.[48] They paraded down the streets of Richmond, albeit without weapons. At least one such review had to be cancelled due not merely to lack of weaponry, but also lack of uniforms or equipment. These units did not see combat; Richmond fell without a battle to Union armies one week later in early April 1865. These two companies were the sole exception to the Confederacy's policy of spurning black soldiery, never saw combat, and came too late in the war to matter.[2] In his memoirs, Davis stated "There did not remain time enough to obtain any result from its provisions".[49]

According to a 2019 study by historian Kevin M. Levin, the origin of the myth of black Confederate soldiers primarily originates in the 1970s.[52] After 1977, some Confederate heritage groups began to claim that large numbers of black soldiers fought loyally for the Confederacy.[53][54] These accounts are not given credence by historians, as they rely on sources such as postwar individual journals rather than military records.[2][53] Historian Bruce Levine wrote:

The whole sorry episode [the mustering of colored troops in Richmond] provides a fitting coda for our examination of modern claims that thousands and thousands of black troops loyally fought in the Confederate armies. This strikingly unsuccessful last-ditch effort constituted the sole exception to the Confederacy's steadfast refusal to employ African American soldiers. As General Ewell's long term aide-de-camp, Major George Campbell Brown, later affirmed, the handful of black soldiers mustered in the southern capital in March of 1865 constituted 'the first and only black troops used on our side.'[55]

Non-military use

[edit]The impressment of slaves and conscription of freedmen into direct military labor initially came on the impetus of state legislatures, and by 1864, six states had regulated impressment (Florida, Virginia, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, in order of authorization).[56][57][58] Slave labor was used in a wide variety of support roles, from infrastructure and mining, to teamster and medical roles such as hospital attendants and nurses.[47]: 62–63 Bruce Levine wrote that "Nearly 40% of the Confederacy's population were unfree... the work required to sustain the same society during war naturally fell disproportionately on black shoulders as well. By drawing so many white men into the army, indeed, the war multiplied the importance of the black work force."[47]: 62

Naval historian Ivan Musicant wrote that blacks may have possibly served various petty positions in the Confederate Navy, such as coal heavers or officer's stewards, although records are lacking.[59]

After the war, the State of Tennessee granted Confederate pensions to nearly 300 African Americans for their service to the Confederacy.[60][61]

Proposals to arm slaves

[edit]The idea of arming slaves for use as soldiers was speculated on from the onset of the war, but not seriously considered by Davis or others in his administration. As the Union saw victories in the fall of 1862 and the spring of 1863, however, the need for more manpower was acknowledged by the Confederacy in the form of conscription of white men, and the national impressment of free and enslaved blacks into laborer positions. State militias composed of freedmen were offered, but the War Department spurned the offer.[47]: 19

Will the slaves fight?−the experience of this war so far has been that half-trained Negroes have fought as bravely as half-trained Yankees.

In January 1864, General Patrick Cleburne in the Army of Tennessee proposed using slaves as soldiers in the national army to buttress falling troop numbers. Cleburne recommended offering slaves their freedom if they fought and survived. He also recommended recognizing slave marriages and family, and forbidding their sale, hotly controversial proposals when slaveowners routinely separated families and refused to recognize familial bonds. Cleburne cited the blacks in the Union army as proof that they could fight. He also believed that such a policy would reduce mass defections of slaves to the Union: "The approach of the enemy would no longer find every household surrounded by spies ... There would be no recruits awaiting the enemy with open arms, no complete history of every neighborhood with ready guides, no fear of insurrection in the rear...[2]

Cleburne's proposal received a hostile reception. Recognizing slave families would entirely undermine the economic foundation of slavery, as a man's wife and children would no longer be salable commodities, so his proposal veered too close to abolition for the pro-slavery Confederacy.[2] The other officers in the Army of Tennessee disapproved of the proposal. A. P. Stewart said that emancipating slaves for military use was "at war with my social, moral, and political principles", while James Patton Anderson called the proposal "revolting to Southern sentiment, Southern pride, and Southern honor."[63][64][2] It was sent to Confederate President Jefferson Davis anyway, who refused to consider Cleburne's proposal and ordered the report kept private as discussion of it could only produce "discouragement, distraction, and dissension." Military adviser to Davis General Braxton Bragg considered the proposal outright treasonous to the Confederacy.[2]

The growing setbacks for the Confederacy in late 1864 caused a number of prominent officials to reconsider their earlier stance, however. President Lincoln's re-election in November 1864 seemed to seal the best political chance for victory the South had. President Davis, Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin, and General Robert E. Lee now were willing to consider modified versions of Cleburne's original proposal. On November 7, 1864, in his annual address to Congress, Davis hinted at arming slaves.[65] Despite the suppression of Cleburne's idea, the question of enlisting slaves into the army had not faded away but had become a fixture of debate among columns of southern newspapers and southern society in the winter of 1864.[47]: 4 [66] Representative of the two sides in the debate were the Richmond Enquirer and the Charleston Courier:

... whenever the subjugation of Virginia or the employment of her slaves as soldiers are alternative propositions, then certainly we are for making them soldiers, and giving freedom to those negroes that escape the casualties of battle.

— Nathaniel Tyler in the Richmond Enquirer[67]

Slavery, God's institution of labor, and the primary political element of our Confederation of Government, state sovereignty... must stand or fall together. To talk of maintaining independence while we abolish slavery is simply to talk folly.

— Charleston Courier[68]

Opposition to the proposal was still widespread, even in the last months of the war. Howell Cobb of Georgia wrote in January 1865 that

the proposition to make soldiers of our slaves is the most pernicious idea that has been suggested since the war began... You cannot make soldiers of slaves, nor slaves of soldiers... The day you make soldiers of [Negroes] is the beginning of the end of the revolution. If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong – but they won't make soldiers.[64][2]

Robert M. T. Hunter wrote "What did we go to war for, if not to protect our property?"[2] Confederate General Robert Toombs complained "But if you put our negroes and white men into the army together, you must and will put them on an equality; they must be under the same code, the same pay, allowances and clothing. There must be promotions for valor or there will be no morals among them. Therefore, it is a surrender of the entire slavery question."[69]

On January 11, 1865, General Robert E. Lee wrote the Confederate Congress urging them to arm and enlist black slaves in exchange for their freedom.[70] On March 13, the Confederate Congress passed legislation to raise and enlist companies of black soldiers by one vote. The law allowed slaves to enlist, but only with the consent of their slave masters. The legislation was then promulgated into military policy by Davis in General Order No. 14 on March 23, 1865.[44] The war ended less than six weeks later, and there is no record of any black unit being accepted into the Confederate army or seeing combat.[71]

Louisiana militia

[edit]Louisiana was somewhat unique among the Confederacy as the Southern state with the highest proportion of non-enslaved free blacks, a remnant of its time under French rule. Elsewhere in the South, such free blacks ran the risk of being accused of being a runaway slave, arrested and enslaved. One of the state militias was the 1st Louisiana Native Guard, a militia unit composed of free men of color, mixed-blood creoles who would be considered black elsewhere in the South by the one-drop rule. The unit was short lived, and never saw combat before forced to disband in April 1862 after the Louisiana State Legislature passed a law that reorganized the militia into only "...free white males capable of bearing arms."[72][73] The militia was later briefly reformed, then dissolved again. A Union army regiment 1st Louisiana Native Guard, including some former members of the former Confederate 1st Louisiana Native Guard, was later formed under the same name after General Butler took control of New Orleans.

Other militias with notable free black representation included the Baton Rouge Guards under Capt. Henry Favrot, the Pointe Coupee Light Infantry under Capt. Ferdinand Claiborne, and the Augustin Guards and Monet's Guards of Natchitoches under Dr. Jean Burdin. The only official duties ever given to the Natchitoches units were funeral honor guard details.[74] One account of an unidentified African American fighting for the Confederacy, from two Southern 1862 newspapers,[75] tells of "a huge negro" fighting under the command of Confederate Major General John C. Breckinridge against the 14th Maine Infantry Regiment in a battle near Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on August 5, 1862. The man was described as being "armed and equipped with knapsack, musket, and uniform", and helping to lead the attack.[76] The man's status of being a freedman or a slave is unknown.

Out of a total of 18,547 free blacks in Louisiana in 1860, between 2,000 and 3,000 volunteered for military service for the Confederacy.[77]

Confederate Navy

[edit]There is evidence of a small number enslaved and free African Americans who were sailors/laborers (though not combatants necessarily) in the Confederate Navy. This includes a sailor named Edward Weeks who served on the CSS Alabama.[78] Typically tasks in the Confederate navy were those of menial labor. Historians have estimated that up to 5% of seamen on Confederate ships in Savannah were of African American descent. These numbers were always small, and were limited by officials in the Confederate government.[79]

United States Colored Troops as prisoners of war

[edit]Prisoner exchanges between the Union and Confederacy were suspended when the Confederacy refused to return black soldiers captured in uniform. In October 1862, the Confederate Congress issued a resolution declaring that all Negroes, free and enslaved, should be delivered to their respective states "to be dealt with according to the present and future laws of such State or States".[80] In a letter to General Beauregard on this issue, Secretary Seddon pointed out that "Slaves in flagrant rebellion are subject to death by the laws of every slave-holding State" but that "to guard, however, against possible abuse...the order of execution should be reposed in the general commanding the special locality of the capture."[81]

However, Seddon, concerned about the "embarrassments attending this question",[82] urged that former slaves be sent back to their owners. As for freemen, they would be handed over to Confederates for confinement and put to hard labor.[83] Black troops were actually less likely to be taken prisoner than whites, as in many cases, such as the Battle of Fort Pillow, Confederate troops murdered them on the battlefield; if taken prisoner, black troops and their white officers faced far worse treatment than other prisoners.

In the last few months of the war, the Confederate government agreed to the exchange of all prisoners, white and black, and several thousand troops were exchanged until the surrender of the Confederacy ended all hostilities.[84] Some African Americans joined the U.S. Army as soldiers, while others were employed as laborers, scouts, and servants. In the navy, African American sailors played crucial roles aboard ships. Their participation was often overlooked and not formally documented in many cases. For more click here.

See also

[edit]- German Americans in the American Civil War

- Hispanics in the American Civil War

- Irish Americans in the American Civil War

- Italian Americans in the Civil War

- Native Americans in the American Civil War (Cherokee, Choctaw)

- Social history of soldiers and veterans in the United States

- William Carney, the first African-American to receive the Medal of Honor.[12]

- Martin R. Delany, the first black commanding officer to serve in the Union Army[85]

- A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, 1861–1865, 1888 history by George Washington Williams

- Louisiana Battalion of Free Men of Color.

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b c Aptheker, Herbert (January 1947). "Negro Casualties in the Civil War". The Journal of Negro History. 32 (1): 12. doi:10.2307/2715291. hdl:2027/mdp.39015026808827. JSTOR 2715291. S2CID 149567737.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bonekemper III, Edward (2015). The Myth of the Lost Cause. New York: Regnery Publishing. pp. 78–92. ISBN 978-1-62157-454-5.

- ^ Bruce Levine, "Black Confederates", North & South 10#2 pp. 40–45.

- ^ "Douglass Monthly" V (August 1863) 852

- ^ a b c James McPherson, "The Negro's Civil War".

- ^ Edward G. Longacre, "Black Troops in the Army of the James", 1863–65 "Military Affairs", Vol. 45, No. 1 (February 1981), p.3

- ^ "Teaching With Documents: The Fight for Equal Rights: Black Soldiers in the Civil War". National Archives. The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ^ Trudeau, Noah A., Like Men of War, Little, Brown and Company, p.8-9.

- ^ U.S. Statutes at Large XII, p. 589-92

- ^ "Black Civil War Soldiers - Facts, Death Toll & Enlistment". 22 November 2022.

- ^ Brabson, Fay Warrington (1972). Andrew Johnson: a life in pursuit of the right course, 1808–1875: the seventeenth President of the United States. Durham, N.C.: Seeman Printery. p. 96. LCCN 77151079. OCLC 590545. OL 4578789M.

- ^ a b "Black Soldiers in the Civil War". Archives.gov. 2011-10-19. Retrieved 2012-05-27.

- ^ Butts, Heather (2005). "Alexander Thomas Augusta Physician, Teacher and Human Rights Activist". J Natl Med Assoc. 97 (1): 106–9. PMC 2568562. PMID 15719881.

- ^ Jane E. Schultz, "Seldom Thanked, Never Praised, and Scarcely Recognized: Gender and Racism in Civil War Hospitals", Civil War History, Vol. xlviii No. 3 p. 221

- ^ "The Color of Bravery". American Battlefield Trust. 2013-07-29. Retrieved 2021-05-30.

- ^ Official Record of the War of the Rebellion Series I, Vol. XXVI, Pt. 1, p. 45

- ^ Rogers, Octavia V., "The House of Bondage", Oxford University Press, pg.131.

- ^ Trudeau, Noah A., Like Men of War, Little, Brown and Company, p.37.

- ^ "Milliken's Bend". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved 2021-05-30.

- ^ a b "Battle of Milliken's Bend, June 7, 1863 - Vicksburg National Military Park (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "New York Tribune,", September 8, 1865

- ^ Ward, Thhomas J. Jr. (August 27, 2013). "The Plight of the Black P.O.W." The New York Times. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ^ Trudeau, Noah A., Like Men of War, Little, Brown and Company, p.166-168.

- ^ "Uncovered Photos Offer View of Lincoln Ceremony". NPR.

- ^ Eric Foner. Give Me Liberty!: An American History. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2004, p. 497 ISBN 978-0-393-97873-5

- ^ U.S. Statutes at Large, XIII, 129-131

- ^ "Black Soldiers in the Civil War". Archives.gov. 2011-10-19. Retrieved 2012-05-27.

- ^ Official Record Ser. III Vol. III p. 1126

- ^ "Black Dispatches: Black American Contributions to Union Intelligence During the Civil War". cia.gov. Archived from the original on June 12, 2007. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ Chism, Kahlil (March 2005). "Harriet Tubman: Spy, Veteran, and Widow". OAH Magazine of History. 19 (1): 47–51. doi:10.1093/maghis/19.2.47.

- ^ "African Americans In The Civil War". HistoryNet. Retrieved 2021-05-30.

- ^ "Patrick Cleburne's Proposal to Arm Slaves". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved 2021-05-30.

- ^ "African Americans in the U.S. Navy During the Civil War".

- ^ Steven J. Ramold. Slaves, Sailors, Citizens pp. 3–4

- ^ Official Record of the Confederate and Union Navies, Ser. I vol. VI, Washington, 1897, pp. 8–10. See http://cdl.library.cornell.edu/moa/browse.monographs/ofre.html

- ^ Ramold, Slaves, Sailors, Citizens, p. 55

- ^ Ramold, Slaves, Sailors, Citizens, pp. 82–84.

- ^ Ramold, Slaves, Sailors, Citizens, pp. 92–99.

- ^ Ramold, Slaves, Sailors, Citizens, pp. 76–77.

- ^ "Robert Smalls, from Escaped Slave to House of Representatives – African American History Blog – The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross". PBS. 13 January 2013.

- ^ Editors, Peter Wallenstein and Bertram Wyatt-Brown. Lucinda H. Mackethan. "Reading Marlboro Jones: A Georgia Slave in Civil War Virginia", Virginia's Civil War. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2005.

- ^ Smith, Sam (10 February 2015). "Black Confederates". American Battlefield Trust. Civil War Trust.

- ^ Martinez, Jaime Amanda. "Black Confederates". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities Council.

- ^ a b Official Record, Series IV, Vol. III, p. 1161-1162.

- ^ Davis, William C., Jefferson Davis: The Man and His Hour, p. 599.

- ^ Statement of the Auditor of the Numbers of Slaves Fit for Service, March 25, 1865, William Smith Executive Papers, Virginia Governor's Office, RG 3, State Records Collection, LV.

- ^ a b c d e Bruce Levine. Confederate Emancipation: Southern Plans to Free and Arm Slaves during the Civil War.

- ^ James M. McPherson, ed., The Most Fearful Ordeal: Original Coverage of the Civil War by Writers and Reporters of the New York Times, p. 319.[1]

- ^ Jefferson Davis, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. p. 518

- ^ "Jefferson Shields profile in Richmond paper, Nov. 3, 1901". The Daily Times. 1901-11-03. p. 18. Retrieved 2022-03-01.

- ^ Levin, Kevin (2019). Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War's Most Persistent Myth. UNC Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-1-4696-6941-0.

- ^ Levin, Kevin M. (2019). Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War's Most Persistent Myth. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-5326-6.

- ^ a b Levin, Kevin (August 8, 2015). "The Myth of the Black Confederate Soldier". The Daily Beast. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ^ Marshall, Josh (January 2, 2018). "In Search of the Black Confederate Unicorn". Talking Points Memo. TPM Media LLC. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ Levine, Bruce. "Black Confederates", North & South 10, no. 2. p. 40–45.

- ^ Bergeron, Arthur W., Jr. Louisianans in the Civil War, "Louisiana's Free Men of Color in Gray", University of Missouri Press, 2002, p. 109.

- ^ Bernard H. Nelson, "Confederate Slave Impressment Legislation, 1861–1865", The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 31, No. 4. (October, 1946), pp. 393–394.

- ^ Nelson, "Confederate Slave Impressment Legislation," p. 398.

- ^ Ivan Musicant, "Divided Waters: The Naval History of the Civil War". (1995) p. 74. "Free blacks could enlist with the approval of the local squadron commander, or the Navy Department, and slaves were permitted to serve with their master's consent. It was stipulated that no draft of seamen to a newly commissioned vessel could number more than 5 per cent blacks. Though figures are lacking, a fair number of blacks served as coal heavers, officers' stewards, or at the top end, as highly skilled tidewater pilots."

- ^ "Tennessee State Library & Archives – Tennessee Secretary of State". Archived from the original on 2012-03-07. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- ^ "Tennessee Colored Pension Applications for CSA Service".

- ^ Official Record, Series I, Vol. LII, Part 2, pp. 586–592.

- ^ Official Record, Series I, Vol. LII, Pt. 2, p. 598.

- ^ a b Official Record, Series IV, Vol III, p. 1009.

- ^ Fellman, Michael; Gordon, Lesley Jill; Sutherland, Daniel E. (2008). This Terrible War: The Civil War and its Aftermath (2nd ed.). New York: Pearson Longman.

- ^ Thomas Robson Hay. "The South and the Arming of the Slaves", The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 6, No. 1. (June, 1919), p. 34.

- ^ Richmond Enquirer, October 6, 1864

- ^ Charleston Courier, January 24, 1865

- ^ ""It Is a Surrender Of the Entire Slavery Question"". civil war memory. 2014-11-13. Retrieved 2021-05-30.

- ^ Official Record. Series IV, Vol. III, p. 1012-1013.

- ^ "Black Confederates: Truth and Legend". 10 February 2015.

- ^ Official copy of the militia law of Louisiana, adopted by the state legislature, Jan. 23, 1862

- ^ Hollandsworth, James G., The Louisiana Native Guards, LSU Press, 1996, p.10.

- ^ Bergeron, Arhur W., Jr. Louisianans in the Civil War, "Louisiana's Free Men of Color in Gray", University of Missouri Press, 2002, p. 107-109.

- ^ Daily Delta, August 7, 1862; Grenada (Miss.) Appeal, August 7, 1862

- ^ Bergeron, Arhur W., Jr. Louisianans in the Civil War, "Louisiana's Free Men of Color in Gray", University of Missouri Press, 2002, p. 108.

- ^ John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, p.34 (Louisiana State University Press 1991) (retrieved June 23, 2024); Arthur W. Bergeron, Jr., Louisianans in the Civil War, p.110 (University of Missouri Press 2002) (retrieved June 23, 2024) (stating that Winters's figure of 3,000 should be reduced to 2,000).

- ^ Dr. Wilbert L. Jenkins: Climbing Up to Glory: A Short History of African Americans During the Civil War and Reconstruction (SR Books, 2002), p. 72.

- ^ Barbara Tomblin, Life in Jefferson Davis' Navy (Naval Institute Press, 2019)

- ^ Statutes at Large of the Confederate State (Richmond 1863), 167–168.

- ^ Official Record, Series II, Vol. VIII, p. 954.

- ^ Official Record, Series II, Vol. VI, pp. 703–704.

- ^ "Treatment of Colored Union Troops by Confederates, 1861–1865", The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 20, No. 3. (July, 1935), pp. 278–279.

- ^ Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 457.

- ^ "Delany, Martin R. (1812–1885)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 2012-05-27.

Bibliography

- Kevin M. Levin, Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War's Most Persistent Myth. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

- Jaime Amanda Martinez, Confederate Slave Impressment in the Upper South. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

- Bruce Levine, Confederate Emancipation: Southern Plans to Free and Arm Slaves During the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. review by David W. Blight.

Further reading

[edit]- Dobak, William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2013. ISBN 978-1-61608-839-2

- Levin, Kevin M. "Black Confederates Out of the Attic and Into the Mainstream" Journal of the Civil War Era 4#4 (2014), pp. 627-635 https://doi.org/10.1353/cwe.2014.0073

- Mendez, James G. A Great Sacrifice: Northern Black Soldiers, Their Families, and the Experience of Civil War. New York: Fordham University Press, 2019. ISBN 9780823282500

- Smith, John David. Lincoln and the U.S. Colored Troops. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-8093-3290-8